Introduction-

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797–1869), revered as one of the greatest Urdu and Persian poets, was a literary giant whose ghazals and letters captured the soul of 19th-century India with unmatched wit, depth, and emotional resonance. Known as the “King of Ghazal,” Ghalib’s poetry explored love, loss, and existential musings, while his prose chronicled the decline of Mughal India amidst British colonialism. His life, marked by financial struggles and personal tragedies, was a testament to resilience and creative brilliance. This biography delves into Ghalib’s multifaceted journey, his revolutionary contributions to Urdu literature, and his enduring legacy as a voice of timeless human experience.

Earlylife and Background

Birth and Family:

Ghalib was born on December 27, 1797, in Agra, Mughal India, as Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan. His father, Mirza Abdullah Baig Khan, was a military officer of Turkic descent who died when Ghalib was five. His mother, Izzat-un-Nisa Begum, came from a distinguished family. After his father’s death, Ghalib was raised by his uncle, Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan, a nobleman in Agra. Ghalib had an elder brother, Mirza Yusuf, who suffered from mental illness, and no recorded siblings beyond this.

Childhood and Education:

-Orphaned early, Ghalib grew up in Agra under his uncle’s care, receiving a traditional education in Persian, Arabic, and Urdu from tutors like Mullah Abdus Samad, a Persian scholar who fled to India.

He displayed a precocious talent for poetry, composing his first verses at age 11, initially in Persian, reflecting the cultural prestige of the language in Mughal courts. At 13, Ghalib moved to Delhi, a vibrant literary and cultural hub, where he immersed himself in the city’s poetic circles and refined his craft under mentors like Ustad Zainuddin Shirazi.

Formative Influences:

The decline of the Mughal Empire, exacerbated by British expansion after the 1857 Rebellion, shaped Ghalib’s worldview, blending nostalgia for a fading era with sharp social commentary. Persian poets like Hafiz and Bedil profoundly influenced his style, while Urdu poets like Mir Taqi Mir inspired his shift to Urdu as a primary medium. His exposure to Delhi’s cosmopolitan society, including interactions with British officials and Indian nobility, broadened his intellectual horizons.

Personal Life

Personality Traits

Ghalib was witty, introspective, and irreverent, with a sharp intellect and a penchant for humor that masked his inner melancholy. His poetry and letters reveal a man both playful and profoundly philosophical. He was sociable yet fiercely independent, often clashing with patrons over his principles, and struggled with pride in his literary genius amidst financial woes.

Relationships

At 13, Ghalib married Umrao Begum, the daughter of a Delhi noble, in 1810. Their marriage was affectionate but strained by the loss of all seven of their children in infancy, a recurring source of grief.

He maintained close friendships with poets like Momin Khan Momin and intellectuals like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, engaging in lively literary debates at *mushairas* (poetry recitals). Ghalib adopted his nephew, Arif, after Arif’s parents died, but Arif’s death in 1857 deepened Ghalib’s sorrows.

Private Struggles

Chronic financial difficulties plagued Ghalib, as his small pension from the Mughal court and irregular patronage barely sustained his household, leading to debts and legal disputes. He battled alcoholism and gambling, habits that strained his finances and reputation, though he remained unapologetic, writing, “Let me drink, for in wine lies my peace.” The 1857 Rebellion devastated Delhi, leaving Ghalib emotionally and financially scarred, as he witnessed the city’s destruction and the Mughal court’s collapse.

Hobbies and Interests

Ghalib was passionate about chess and kite-flying, pastimes that reflected his playful side and love for Delhi’s cultural traditions. He enjoyed writing letters, which he considered an art form, corresponding with friends and disciples in a style both candid and eloquent. He frequented “mushairas”, where his recitations captivated audiences, and savored Delhi’s culinary and intellectual life.

Social and Cultural Context

Historical Setting:

Ghalib lived during the twilight of the Mughal Empire, as British colonial rule tightened after the East India Company’s victories, culminating in the 1857 Rebellion and the formal end of Mughal sovereignty in 1858. Delhi was a cultural epicenter, hosting vibrant literary salons and Sufi shrines, but faced increasing social and economic strain under colonial policies. The rise of Urdu as a literary language, alongside Persian’s decline, marked a linguistic shift that Ghalib both shaped and reflected.

Social Role:

As a Muslim nobleman of Turkic descent, Ghalib navigated Mughal and British elites, serving as a court poet and historian under Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II. His multilingual fluency (Urdu, Persian, Arabic) and engagement with diverse communities—Muslim, Hindu, and British—made him a cultural intermediary. He challenged literary conventions, elevating Urdu poetry to new heights while critiquing societal decay and colonial oppression.

Public Perception:

During his lifetime, Ghalib was admired in Delhi’s literary circles but underappreciated by the broader public, who favoured simpler poets like Zauq, the court poet laureate. His complex Persian poetry alienated some readers, though his Urdu ghazals gained traction later in life, especially after publication.

Posthumously, Ghalib became an icon of Urdu literature, celebrated as a national treasure in India and Pakistan.

Career and Achievements

Early Career:

Ghalib began composing poetry in his teens, initially in Persian, publishing his first “divan” (poetry collection) at 19. He adopted the pen name “Ghalib” (meaning “dominant” or “victor”). In his 20s, he joined Delhi’s poetic circles, competing in “mushairas” and gaining patronage from nobles, though financial instability persisted. He briefly travelled to Calcutta (1828–1830) to appeal for a pension, engaging with British officials and local poets, which broadened his literary exposure.

Major Achievements:

– Authored “Diwan-e-Ghalib”, a collection of Urdu ghazals, refined over decades, with around 1,800 couplets known for their philosophical depth and lyrical beauty.

– Published “Nuskha-e-Hamidiya” (1850), his definitive Urdu “divan”, which elevated the ghazal form with themes of love, mortality, and existential inquiry.

– Wrote extensive Persian poetry, including “Qadir-nama” and “Chiragh-e-Dair”, though his Persian works were less popular than his Urdu.

– Composed “Dastanbuy” (1858), a Persian prose account of the 1857 Rebellion, commissioned by the British, showcasing his historical insight.

– Produced “Urdu-e-Mualla”, a collection of over 700 letters, considered a literary masterpiece for their wit, candor, and stylistic innovation, revolutionizing Urdu prose.

Innovations and Ideas:

– Transformed the Urdu ghazal by infusing it with philosophical and existential themes, moving beyond conventional love poetry to explore human condition.

– Pioneered a conversational prose style in his letters, making Urdu a vibrant medium for personal expression, influencing later writers like Premchand.

– Blended Persianate sophistication with Indian vernacular, creating a unique poetic voice that bridged cultures.

Collaborations and Rivalries:

– Collaborated with Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, serving as his poetry tutor and court historian, and corresponded with intellectuals like Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi.

– Engaged in a literary rivalry with Ibrahim Zauq, whose simpler style overshadowed Ghalib’s during their lifetimes, though Ghalib’s wit prevailed in anecdotes.

– Mentored younger poets like Altaf Hussain Hali, who later popularized Ghalib’s work through critical biographies.

Impact and Legacy

Immediate Impact:

Ghalib’s Urdu ghazals revitalized Delhi’s literary scene, inspiring poets to explore deeper themes, though his full recognition came posthumously. His letters documented the cultural and social life of Mughal Delhi, preserving a vanishing world for future generations. His role as a court poet strengthened Urdu’s prestige in the Mughal court, despite British dominance.

Long-Term Legacy:

– Ghalib is celebrated as the cornerstone of Urdu poetry, with “Diwan-e-Ghalib” a staple in South Asian literature, translated into English, Hindi, and other languages.

– His letters are studied as a literary genre, influencing modern Urdu prose and earning praise from scholars like Muhammad Sadiq as “the first great prose writer in Urdu.”

– Institutions like the Ghalib Academy in Delhi and the Ghalib Institute preserve his manuscripts, letters, and legacy through publications and events.

– His poetry inspired Bollywood songs, TV serials (e.g., “Mirza Ghalib” by Gulzar, 1988), and modern adaptations, cementing his cultural presence.

Criticism and Controversies:

– Some contemporaries criticized Ghalib’s complex style as elitist, preferring Zauq’s accessibility, though later critics like Hali championed his depth.

– His acceptance of British patronage post-1857, including writing “Dastanbuy”, drew accusations of opportunism, though he defended it as a means of survival.

– Modern debates explore whether Ghalib’s secular humanism overshadowed his Muslim identity, with scholars like Ralph Russell emphasizing his universal appeal.

Modern Relevance:

– Ghalib’s ghazals, like “Hazaron khwahishen aisi” and “Dil-e-nadan tujhe hua kya hai,” remain widely recited, quoted in social media, and featured in music (e.g., Jagjit Singh’s renditions).

– His reflections on loss and resilience resonate in contemporary South Asia, addressing themes of identity and change.

– Documentaries like “Mirza Ghalib: The Playful Muse” (2007) and platforms like Rekhta.org popularize his work, while X posts frequently share his couplets, such as “Ishq ne Ghalib nikamma kar diya, warna hum bhi aadmi the kaam ke.”

– His Delhi haveli, restored as a museum, attracts literary pilgrims, affirming his enduring stature.

Ideas and Philosophy

Core Beliefs:

– Ghalib’s philosophy blended Sufi mysticism with rational skepticism, exploring the tension between divine will and human desire, as seen in lines like “Na tha kuchh to Khuda tha, kuchh na hota to Khuda hota.”

– He championed individual freedom and self-expression, critiquing societal hypocrisy and rigid traditions while embracing life’s contradictions.

– His secular humanism celebrated universal human experiences, transcending religious and cultural divides.

Key Writings or Speeches:

– Diwan-e-Ghalib: A collection of ghazals exploring love, loss, and existential questions, with couplets like “Yeh na thi hamari qismat ke visal-e-yaar hota.”

–“Urdu-e-Mualla”: Letters to friends and disciples, blending humour, philosophy, and social commentary, considered a landmark in Urdu prose.

-“ Dastanbuy”: A Persian prose work chronicling the 1857 Rebellion, reflecting Ghalib’s nuanced perspective on colonial upheaval.

– Famous quote: “Bazeecha-e-atfal hai duniya mere aage, hota hai shab-o-roz tamasha mere aage” (The world is a child’s play before me, a spectacle unfolds day and night).

Influence on Others:

– Inspired modernist Urdu poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Ahmad Faraz, who adopted his introspective style.

– Influenced literary critics like Altaf Hussain Hali, whose “Yadgar-e-Ghalib” elevated Ghalib’s posthumous fame.

– Shaped Urdu prose through his letters, paving the way for narrative styles in South Asian literature.

Anecdotes and Defining Moments

Pivotal Events:

– In 1828, Ghalib’s journey to Calcutta exposed him to British culture and Bengali poets, enriching his Urdu style and inspiring poems like “Chiragh-e-Dair”, a tribute to Benares.

– The 1857 Rebellion marked a turning point, as Ghalib witnessed Delhi’s destruction, writing poignantly in his letters, “Delhi is no more a city, but a camp, a cantonment.”

Lesser-Known Stories:

– When challenged by Zauq at a “mushaira”, Ghalib improvised a ghazal that outshone his rival, earning applause and cementing his reputation.

– He once humorously rebuffed a British official’s request for flattery, saying, “I am a poet, not a courtier,” showcasing his integrity.

Quotes:

– “Hui muddat ke Ghalib mar gaya, par yaad aata hai, woh har ek baat par kehna ke yun hota to kya hota.”

– “Dard-e-dil likhoon kab tak, jaaun un se kah doon, ik baar keh do mujh se ke dil se dil tak baat jati hai.”

Visual and Archival Elements

[Haveli of Mirza Ghalib, Delhi.]

Photographs and Artifacts:

– Portraits of Ghalib, based on descriptions, depict him in a Mughal cap and robe, preserved at the Ghalib Academy in Delhi.

– His haveli in Delhi’s Ballimaran, restored as a museum, displays manuscripts, letters, and personal items like his hookah.

Letters and Documents:

– Manuscripts of “Diwan-e-Ghalib” and “Urdu-e-Mualla”, housed at Aligarh Muslim University and the National Archives of India, showcase his elegant calligraphy.

– His Persian “divan” and “Dastanbuy” are digitized by Rekhta.org, offering access to his lesser-known works.

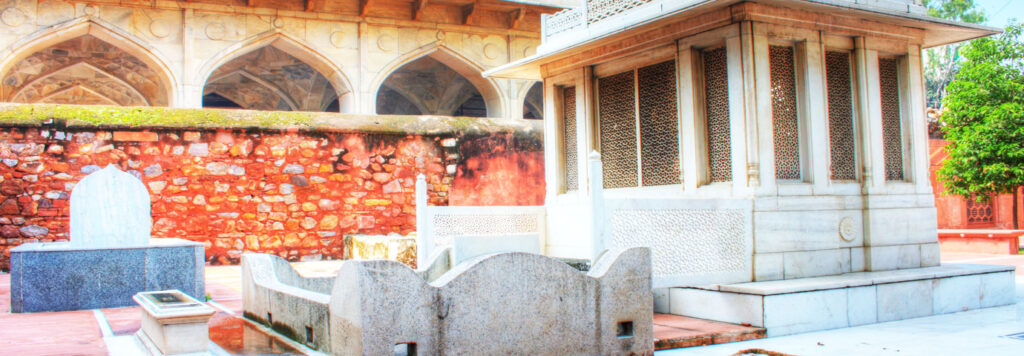

[Tomb of Mirza Ghalib, Delhi.]

Timeline

– 1797: Born in Agra.

– 1810: Marries Umrao Begum; moves to Delhi.

– 1828–1830: Travels to Calcutta.

– 1850: Publishes “Nuskha-e-Hamidiya”.

– 1857: Witnesses the Rebellion.

– 1869: Dies in Delhi on February 15.

Conclusion

Mirza Ghalib’s life was a tapestry of brilliance and adversity, weaving poetry and prose that captured the heart of a crumbling empire and the soul of humanity. His ghazals and letters, rich with wit and wisdom, continue to resonate, offering solace and insight across generations. Readers are invited to explore Ghalib’s *Diwan* on Rekhta.org, visit his haveli in Delhi, or reflect on his timeless question: “Yun hota to kya hota?” (If it had been so, what would it have been?). As Ghalib wrote, “The world is a spectacle before me”—a call to embrace life’s fleeting beauty.

Sources:

Bibliography:

– Russell, Ralph, and Khurshidul Islam. Ghalib: Life and Letters. Oxford, 1994.

– Hali, Altaf Hussain. Yadgar-e-Ghalib. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli, 1897.

– Sadiq, Muhammad. A History of Urdu Literature. Oxford, 1964.

Further Reading:

– Ghalib: The Man, The Times by Pavan K. Varma. Penguin, 1989.

– Documentary: Mirza Ghalib: The Playful Muse (2007, Sahitya Akademi).

– Website: Rekhta.org for Ghalib’s poetry and letters.

Glossary:

– Ghazal: A poetic form of rhymed couplets expressing love or loss.

– Mushaira: A poetic symposium for recitations.

– Divan: A collection of poetry.