The Enduring Power of Awe in Art and Life

Why do we feel a sense of wonder when staring at a stormy sea or a vast mountain range? For the Romantic poets of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, this feeling was more than just appreciation. They called it the sublime—an experience of awe, terror, and transcendence that revealed deeper truths about ourselves and the world.

This blog post explores the concept of the sublime in Romantic poetry. We will look at its historical roots, how poets like Wordsworth and Shelley used nature to evoke it, and why this centuries-old idea still matters today.

What is Romanticism?

Romanticism was a powerful artistic and intellectual movement that swept across Europe. It emerged as a reaction against the Enlightenment’s focus on pure reason and the dehumanizing effects of the Industrial Revolution. Romantics believed that emotion, imagination, and individual experience were the most authentic paths to understanding.

They saw nature not as a passive backdrop but as a living, spiritual force. For them, the unspoiled wilderness offered an escape from the noise and corruption of rapidly growing cities. In nature, they found a mirror for the soul and a connection to something infinite.

The Philosophical Idea of the Sublime

The Romantics didn’t invent the concept of the sublime, but they perfected its use in poetry. The idea has deep philosophical roots.

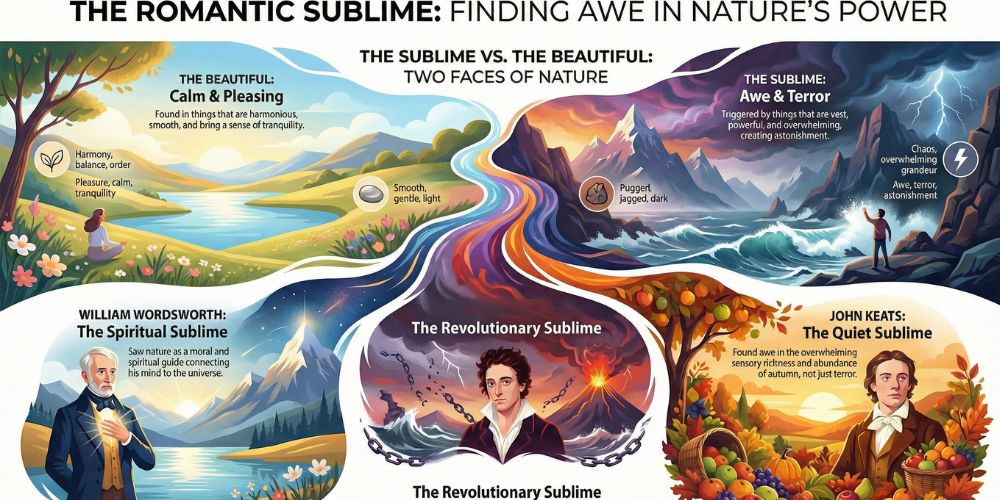

- Edmund Burke: In his 1757 work, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Burke made a crucial distinction. The beautiful, he argued, is found in things that are harmonious, smooth, and pleasing. The sublime, in contrast, is rooted in feelings of terror and awe. It is triggered by things that are vast, powerful, and overwhelming, like a raging storm or a towering cliff. From a position of safety, we can experience a thrilling sense of astonishment.

- Immanuel Kant: A few decades later, the philosopher Immanuel Kant took this idea a step further. In his Critique of Judgment (1790), he suggested the sublime isn’t in the object itself, but in our minds. When we confront something in nature that is too vast for our senses to grasp, we feel our own limitations. However, this initial feeling of being overwhelmed gives way to a realization of the power of human reason to comprehend such concepts, affirming our own inner strength.

The Romantics seized on this powerful emotional cocktail. The sublime allowed them to explore the intense feelings, spiritual questions, and existential anxieties that defined their era. It was the perfect vehicle for expressing the inexpressible.

The Beautiful vs. The Sublime

|

The Beautiful |

The Sublime |

|

Harmony, balance, order |

Chaos, overwhelming grandeur |

|

Pleasure, calm, tranquility |

Awe, terror, astonishment |

|

Finite, small, comprehensible |

Infinite, boundless, obscure |

|

Smooth, gentle, light |

Rugged, jagged, dark |

Nature as a Gateway to the Sublime

Romantic poets used the natural world as their primary stage for exploring the sublime. They saw wild landscapes as a place to confront fundamental truths about life, death, and divinity.

William Wordsworth and the Spiritual Sublime

William Wordsworth saw nature as a moral and spiritual guide. In his famous poem, Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, he describes returning to a beautiful valley. The memory of this landscape has sustained him for years, offering “tranquil restoration” in the Chaos of city life.

More than just seeing the scenery, Wordsworth feels a “presence” that moves through all things. He connects the power of the landscape to his own consciousness, finding a sublime sense of unity between nature, his mind, and the universe. For him, nature was a path to a profound spiritual awakening.

Percy Bysshe Shelley and the Revolutionary Sublime

For Percy Bysshe Shelley, the sublime was a force of change. His “Ode to the West Wind” addresses the wind as a “Wild Spirit” that is both a “destroyer and preserver.” The wind’s power to scatter dead leaves and carry seeds is a metaphor for political and social revolution.

Shelley longs to merge with this power, asking the wind to “Be thou, Spirit fierce, / My spirit!” He wants his words to be scattered across the world like leaves, inspiring change and awakening new ideas. Here, the sublime power of nature is fused with the revolutionary power of poetry.

John Keats and the Quiet Sublime

The sublime isn’t always about storms and terror. John Keats found it in the quiet, overwhelming abundance of Autumn. In his ode To Autumn, he paints a picture of “mellow fruitfulness” and “plenteous harvest.” The poem’s rich, sensuous details are almost overwhelming.

This isn’t the terror of Burke’s sublime, but an awe inspired by the sheer fullness of life at its peak, tinged with the melancholy of its inevitable end. Keats shows us that tranquility can be just as profound and overwhelming as a tempest, creating a sublime experience through contemplation and sensory richness.

Why the Sublime Still Resonates

The Romantic fascination with nature and the sublime may seem distant, but it has had a lasting impact. It shaped the work of later writers, from American Transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau to modern nature authors. The core idea—finding deep personal meaning in the natural world—is still a powerful theme.

More importantly, the sublime offers a vital counterpoint to our digitally saturated lives. It reminds us of the value of stepping away from our screens to confront something raw, vast, and real. In a world we constantly try to control and manage, the sublime reminds us of our own smallness and connects us to forces far greater than ourselves.

This experience can foster humility, reflection, and a sense of wonder. The Romantic poets understood that confronting the overwhelming power of nature is not about escaping the world, but about finding our place within it.

Conclusion

The sublime was a central concept for the Romantic poets, who used nature to explore the deepest corners of human emotion and experience. Through the spiritual presence in Wordsworth‘s valleys, the revolutionary force of Shelley‘s wind, and the serene fullness of Keats’s Autumn, they transformed landscapes into arenas for profound awakening.

In doing so, they left us with a powerful legacy. They teach us that by seeking out experiences of awe—whether in art, nature, or life—we can connect with a sense of wonder that is both humbling and empowering.

Sources

- Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. 1757.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. 1798.

- Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgment. 1790.

- Keats, John. To Autumn. 1820.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Ode to the West Wind. 1820.

- Wordsworth, William. Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey. 1798.

- Wordsworth, William. The Prelude (1850 version).

- Abrams, M.H. Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature. Norton, 1971.

- Brennan, Matthew. Wordsworth, Turner, and Romantic Landscape. Camden House, 1987.

- Shaw, Philip. The Sublime. Routledge, 2006.

- Zimmerman, Sarah. Romanticism, Lyricism, and History. SUNY Press, 1999.