Introduction

Key focus: What this guide will help you do.

Some novels entertain; others quietly change how you see yourself and the world. R. K. Narayan‘s The Guide (1958) firmly belongs to the second category. The story follows Raju, a small-town tour guide who, by accident and misunderstanding, becomes a revered spiritual leader. Beneath the simple premise is one of Indian fiction’s richest explorations of identity, deception, love, ambition, and redemption.

The Guide is more than a set text. It invites you to think about the relationship between storytelling and truth, as well as the gap between society’s roles and true identity. The novel asks difficult questions: Can a fraud become a saint? Can enough self-deception become genuine? Can someone who has spent a lifetime fooling himself and others be redeemed? Narayan does not neatly answer, which makes the novel enduring and rich for literary study.

This article supports your reading of The Guide with depth and rigour. It presents the biographical and historical context shaping the novel. You will find chapter summaries, critical commentary linking episodes to larger themes, and analysis of characters, tone, structure, and meaning. The aim is not to offer ready-made conclusions but to help you form your own nuanced response to a masterwork of Indian writing in English.

Read this article alongside the text, not instead of it. The most productive literary study happens in the movement between primary text and secondary analysis — always returning to Narayan‘s own words as your ultimate source of evidence and pleasure.

Key takeaways

- The Guide explores how performance and identity intersect, and whether genuine redemption is achievable or illusory.

- This guide supports a detailed analysis of the novel, but does not replace your personal reading experience.

- Your own critical response is central; the key takeaway is that this article offers tools, questions, and frameworks to help you develop it.

Part One: The Author

Key focus: How Narayan’s life and career shape The Guide.

K. Narayan: Life, World, and Literary Vision

Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Narayanaswami — known to the world simply as R. K. Narayan — was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras (now Chennai), in South India. The name by which we know him is itself a kind of fiction, a compression of an unwieldy full name into something more manageable and universal: a small act of the literary simplification that would define his entire career.

Narayan grew up in a middle-class Brahmin family and spent much of his childhood in Mysore. He was raised mainly by his grandmother while his father worked as a headmaster in distant towns. Being cared for by a woman steeped in oral tradition was formative for him. His grandmother, a gifted storyteller, filled his childhood with tales and fables from Hindu epics — the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Narayan later credited her for giving him his earliest and most lasting education in narrative: the art of telling stories with human truth.

He received his formal education at various schools in Madras and eventually graduated from the Maharaja’s College in Mysore (now the University of Mysore) in 1930, after initially failing his examinations—a biographical detail he recalled with characteristic good humour. For a time, he tried teaching, found it unsuitable, and turned to writing, which he had been doing privately for years. His early attempts at journalism and short fiction met with little success until he sent the manuscript of his first novel, Swami and Friends, to his friend and brother-in-law Purna, who sent it on to the British novelist Graham Greene.

Greene‘s support changed everything. He recommended the manuscript to Methuen, which published it in 1935. Swami and Friends introduced the fictional town of Malgudi, loosely based on Mysore. The novel launched the Malgudi series that would occupy Narayan for the rest of his career. With this first novel, a fictional universe took shape and grew richer with each book.

The Malgudi novels include The Bachelor of Arts (1937), The Dark Room (1938), The English Teacher (1945), Mr. Sampath (1949), The Financial Expert (1952), Waiting for the Mahatma (1955), The Guide (1958), The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961), The Vendor of Sweets (1967), The Painter of Signs (1976), A Tiger for Malgudi (1983), and Talkative Man (1986). Narayan also wrote many short stories, collecting them in Malgudi Days and A Horse and Two Goats. He wrote travel books, memoirs (My Days, 1974), and modern English versions of the Ramayana (1972) and Mahabharata (1978). The Guide won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1960, India’s highest honor for literature, and is Narayan’s most celebrated novel internationally. He received the Padma Bhushan, the A.C. Benson Medal, and honorary membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. From 1986 to 1992, he was a nominated member of the Rajya Sabha, India’s upper house of Parliament.

Narayan was often asked why he wrote in English rather than in Kannada or Tamil, which he had grown up with. He answered that English was as much his language as any other. The Indian sensibility could express itself in English without apology. He never wrote like an Englishman but like himself. In doing so, he showed that Indian experience could be fully expressed in English.

Critics compare his fiction to Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, and O. Henry. They cite his precise characterisation, economical language, ironic distance, and deep affection for ordinary people. Like Chekhov, he reveals much in a few pages. Like Faulkner, he created a fictional geography — Malgudi — that feels as real as any actual place.

R.K. Narayan died on May 13, 2001, in Chennai, at ninety-four. He left more than thirty books and the enduring gift of Malgudi — a town that belongs to every reader.

Key takeaways

- Narayan’s Malgudi is a recurring fictional town that anchors The Guide’s setting and atmosphere.

- His storytelling, rooted in oral tradition and everyday life, shapes his gentle irony.

- Narayan’s use of English is a confident, deliberate artistic choice, reflecting his unique voice and not imitation.

Check your understanding

- How might Narayan’s own experiences of education, failure, and career change help you read Raju’s journey?

Part Two: Historical and Political Context

Key focus: How post-independence India and social change inform the novel’s world.

Post-Independence India and the World of The Guide

To read The Guide well, you need to understand the historical moment in which it is set. The novel was published in 1958, a little over a decade after India’s independence from British colonial rule in August 1947. The world Narayan depicts in Malgudi is, therefore, the world of early post-independence India: a country simultaneously freed from one kind of history and uncertain about what its future would look like.

Independence brought hope but also complexity. The new Indian state faced the immense task of nation-building. This included integrating hundreds of princely states such as Mysore (Malgudi’s model), coping with the trauma of Partition, fighting rural poverty, and making choices about modernity. Nehru’s government launched the first Five-Year Plan in 1951, focusing on agriculture and infrastructure. In 1956, the second Plan pushed for heavy industry and rapid industrialisation. Both were shaped by a broadly socialist, state-led vision that would influence Indian life for decades.

In The Guide, the railway transforms Raju’s world and starts his career as a shopkeeper and tour guide. The railway symbolises modernisation in India, both during the colonial era and after independence. Narayan uses irony: the railway brings Raju not just opportunity, but also a life of transactions and commissions, marked by profit from others’ needs.

The novel also engages, with quiet but unmistakable seriousness, with the social structures that post-independence India was attempting to reform. Rosie’s background as a devadasi — a woman from a hereditary community of temple dancers who were, in practice, often in a position of sexual and social vulnerability — is crucial to understanding her character and her situation. The devadasi system, which had roots in temple ritual going back centuries, had by the twentieth century become associated with exploitation and was subject to significant legislative reform. The Devadasi Abolition Act was passed in the Madras Presidency in 1947, the same year as independence, as part of a broader post-independence effort to address caste-based inequalities and the exploitation of women. That Rosie is from this background gives her story a specific historical resonance: she is a woman trying to claim her art on her own terms in a society that has historically defined and constrained her.

Yet Narayan is not a didactic novelist. He does not write tracts or manifestos. He does not give speeches through his characters. His engagement with these social and political realities is oblique, embedded in the texture of individual lives rather than proclaimed from a platform. This was a deliberate artistic choice, and it has sometimes drawn criticism from those who felt that a novelist of his stature ought to have engaged more directly with the political upheavals of his time — the trauma of Partition, the debates about caste and reservation, the tensions of Nehruvian socialism. Unlike his contemporaries Raja Rao, whose Kanthapura (1938) placed the freedom struggle at the heart of its narrative, or Mulk Raj Anand, whose work engaged directly with Marxist social critique, Narayan kept his gaze resolutely on the human individual in the small town.

His defence, implied rather than stated, was that the universal is always particular: that by writing truthfully about the lives of ordinary people in Malgudi, he was, in fact, writing truthfully about the human condition in its broadest sense. The drought that drives the climax of The Guide, with its echoes of real agricultural distress in 1950s rural India, is at once a specific historical condition and a mythic test of human endurance and belief.

This context matters because it enriches your reading without determining it. Knowing why the devadasi reform was significant, knowing what the Five-Year Plans meant for rural India, knowing the political climate of the late 1950s: all of this adds depth and precision to your engagement with the novel’s world. But always remember that Narayan’s primary allegiance is to the individual life, not the historical thesis.

Key takeaways

- The railway and the drought embody post-independence modernisation and crisis.

- Rosie’s devadasi background links gender and reform politics.

- Narayan’s politics are indirect, visible through individual lives rather than overt propaganda.

Check your understanding

- How does knowing about devadasi abolition affect the way you read Rosie’s struggle for artistic freedom?

Part Three: The Title

Key focus: What “guide” means at the literal, ironic, and symbolic levels.

Justifying The Guide: Literal, Ironic, and Symbolic Dimensions

The title, The Guide, is among the most carefully chosen and richly layered in Indian English fiction. At first glance, it seems straightforward: Raju is a tour guide. He shows people around Malgudi, takes them to the caves Marco wishes to study, and earns his living through an expert knowledge of places and routes. The title appears to describe an occupation.

But Narayan is never doing only one thing at a time. The guide, in its deeper resonance, is a spiritual figure: someone who leads others not through physical terrain but through the terrain of life’s difficulties. And it is precisely this role that Raju finds himself occupying when the villagers mistake him for a swami. He becomes, wholly without intending to, a guide in this second and more profound sense — dispensing wisdom he does not quite believe, performing a holiness he has not earned, and yet, in the end, perhaps achieving something of what he only pretended to be.

The title also operates ironically. A guide is supposed to know the way. But Raju, for most of the novel, is profoundly lost. He does not know what he wants, he deceives himself as readily as he deceives others, and his life is shaped more by accident and circumstance than by any coherent purpose. The guide who guides others is himself unguided — which is perhaps Narayan’s most pointed observation about the human condition.

Finally, the title gestures toward the question of self-guidance: the capacity to find one’s own way toward truth and integrity. In the novel’s final pages, Raju seems to find this capacity, undertaking his fast with a sincerity he has never shown before. The guide, at last, guides himself. Whether this constitutes genuine spiritual transformation or whether it is simply the last and most consequential of his performances is a question the novel deliberately refuses to answer, and it is a question worth sitting with as a serious reader.

Key takeaways

- “Guide” refers to Raju’s profession, his spiritual role, and his search for self.

- Irony: the one who guides others often lacks direction himself.

- The title encodes the novel’s central ambiguity about performance and sincerity.

Part Four: Summary of the Novel

Key focus: How the dual narrative (past/present) shapes plot and meaning.

Plot Overview

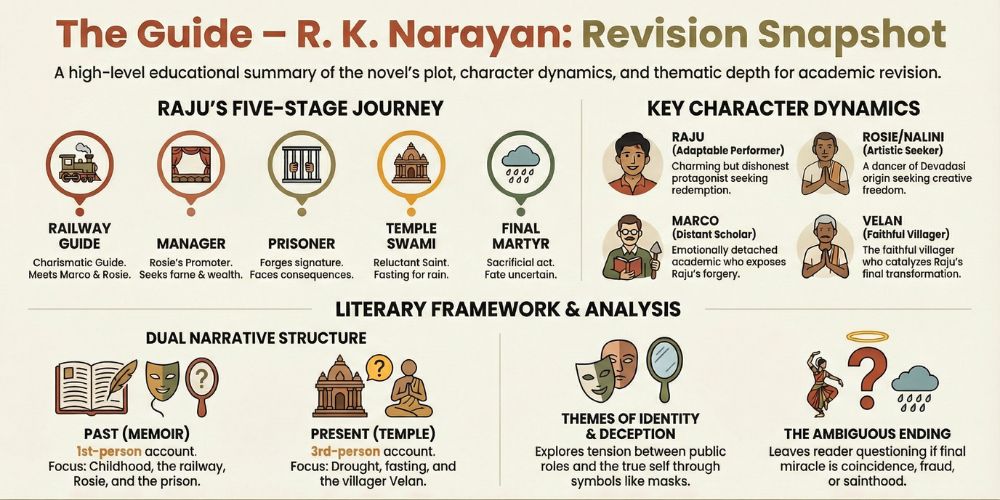

The Guide unfolds through a dual narrative structure: a present-day story told largely in the third person, and an extended flashback told largely in the first person by Raju himself. The interweaving of these two timelines — Raju’s past and Raju’s present — is one of the novel’s most technically accomplished aspects, and understanding how the structure works is essential to understanding what it means.

Presently, Raju has recently been released from prison and has taken shelter in an ancient, partially ruined temple on the banks of the River Sarayu, near the village of Mangal. He is gaunt, tired, and without direction. A villager named Velan stumbles upon him and, seeing a thin man sitting in a temple in an attitude of contemplation, assumes that he is a holy man — a swami. Velan has a problem: his younger sister is refusing to marry the man their family has chosen for her, and he seeks the holy man’s guidance.

Raju, who is genuinely without shelter or resources, takes the path of least resistance. He speaks vaguely and wisely about family harmony, and Velan is satisfied. Word spreads. The village begins to bring Raju food, to decorate the temple, to seek his counsel on matters large and small. Raju finds himself inhabiting, increasingly comfortably, the role of the village’s spiritual guide — a role that requires nothing of him except that he continue to seem wise and holy, tasks for which he discovers he has a considerable natural talent.

Interwoven with this present-day story is the long flashback that makes up the majority of the novel: Raju’s account of his life, from his childhood in Malgudi to his imprisonment. He tells us of his father’s shop near the railway station, of how the coming of the railway transformed his world, of how he developed his identity as “Railway Raju,” the indispensable guide who knew everything about Malgudi and its environs, of how he met the archaeologist Marco and his beautiful, artistic wife Rosie, of how he fell in love with Rosie, encouraged her dancing, became her manager and lover (renaming her Nalini for her stage career), built her to the height of fame, and then destroyed everything through an act of forgery: signing Rosie’s name on documents to access a jewellery box that she had wanted to keep closed.

The forgery is discovered, Marco provides evidence confirming it, and Raju is tried and sentenced to two years in prison. He serves his time, is released, and wanders, directionless, to the temple by the Sarayu where the novel’s present-day action begins.

The crisis comes when a severe drought grips the region. The river dries, crops fail, cattle die, and the villagers grow desperate. In a moment of narrative confusion — one of the novel’s great ironies — Raju finds himself having promised, or appearing to have promised, to fast until rain comes. The village has taken his words as a vow. He is now trapped: renouncing the fast would reveal him as a fraud, but continuing it may kill him.

He confesses his entire past to Velan: his deceptions, his affair, his forgery, his imprisonment. He intends, perhaps, to have Velan release him from the obligation. Instead, Velan hears the confession as a parable of temptation and repentance, entirely consistent with the behaviour of a great holy man. The village’s faith only deepens.

As the novel reaches its end, something has changed in Raju. He is weak and close to death, but he seems to have moved beyond performance into something more genuine. He undertakes the fast with sincerity. In the novel’s final paragraphs, rain begins to fall, and Raju collapses. The ending is deliberately ambiguous: we do not know with certainty whether Raju dies, whether the rain is a coincidence or a miracle, whether Raju has been transformed or has simply found his most convincing performance yet. What we know is that something has ended, and something else — whether it is Raju’s life or Raju’s old self — has ended with it.

Key takeaways

- The novel alternates between Raju’s present as “swami” and his past as “Railway Raju.”

- The drought and the fast provide the novel’s final crisis.

- The ending remains unresolved, forcing readers to decide how far Raju has changed.

Check your understanding

- How does knowing Raju’s full past affect the way you read his actions at the temple?

Part Five: Chapter-by-Chapter Summary and Commentary

Key focus: What each chapter does, and how it contributes to larger themes.

What follows is a chapter-by-chapter account of the novel’s events, combined with critical commentary that identifies the key literary and thematic concerns of each section. Read each summary in conjunction with the text itself, and use the commentary as a prompt for your own analysis rather than as a substitute for it.

Chapter One

Summary

The novel opens in the present, by the Sarayu. Raju has found shelter in the temple. Velan arrives with his domestic problem, receives what he takes to be wisdom, and departs satisfied. The narrative then shifts into the first of its many flashbacks, taking us back to Raju’s childhood in Malgudi: his father’s small shop, the rhythms of family life, the first stirrings of the boy’s personality. The chapter ends with Raju’s rueful acknowledgement that all his present troubles began with Rosie.

Commentary

Narayan‘s opening is structurally brilliant. By beginning in medias res — in the middle of things — with Raju already installed as a holy man, he creates an immediate irony: we know, from the very first pages, that Raju is not what he appears to be. The entire subsequent narrative is therefore coloured by this knowledge. The flashback structure also allows Narayan to modulate between two registers: the comic present (in which Raju dispenses wisdom he does not possess to an audience that asks no difficult questions) and the more complex, more morally ambiguous past (in which Raju made the choices that brought him to this point). The childhood flashback establishes Malgudi as a place of warmth, colour, and recognisable human ordinariness — a world in which Raju’s eventual deceptions will seem all the more poignant.

Chapter Two

Summary

The railway comes to Malgudi. For the young Raju, this is an event of almost mythological significance: a transformation of his known world. He plays among the construction workers, uses rough language, and is punished by his father. He is enrolled in a poly school — a traditional village school held on a veranda — where a strict teacher introduces him to the basics of literacy. The station opens, business booms, and Raju’s childhood shifts from carefree freedom to the first responsibilities of family commerce.

Commentary

The railway is the novel’s central symbol of modernity and its discontents. It offers opportunity, but it also exposes you to a wider, more complex world. The episode in which Raju picks up bad language from the labourers — and is punished for it — is characteristic Narayan: a moment of gentle comedy that carries a more serious point about the costs of progress and the difficulty of protecting one generation from the knowledge that the next generation inevitably absorbs. Raju’s reluctant schooling introduces a theme that will recur throughout the novel: the gap between formal education and genuine wisdom.

Chapter Three

Summary

The railway station becomes the centre of Raju’s world. His father’s shop thrives, Raju is increasingly involved in its management, and he learns the rhythms of business: welcoming travellers, understanding their needs, knowing what to sell and when. His father experiments with a horse-and-carriage service, which proves profitable. Raju gradually takes over more of the shop’s management, effectively dropping out of school without any formal announcement. The chapter ends with Raju fully established as his father’s deputy.

Commentary

This chapter traces the formation of Railway Raju. The station shop is not merely a place of commerce; it is a school of human nature. Every traveller who passes through teaches Raju something about desire, urgency, comfort, and the variability of human need. It is here that he develops the skills — observation, charm, adaptability, the ability to read people quickly and give them what they want to hear — that will later define him both as a tour guide and an accidental saint. Narayan is quietly showing us that Raju’s gifts are real; the question is whether they will be used well or badly.

Chapter Four

Summary

In the present timeline, Raju’s reputation as a holy man has grown substantially. The villagers hail him with increasing fervour. He finds himself organising night classes for the village children in the temple courtyard, a task he approaches with surprising seriousness. A timid schoolteacher assists him. The temple is cleaned, lime-washed, and decorated. Raju distributes gifts and dispenses counsel. He is comfortable, perhaps more comfortable than he has been in years.

Commentary

This chapter is central to understanding the novel’s argument about identity and performance. Raju did not choose to be a saint. He was cast in the role by Velan’s misreading, and he accepted it because it was convenient. But something interesting is happening: in performing the role, he is beginning to embody it, in small ways. His night classes are not a fraud; they are a genuine service to the village. His counsel, however accidentally arrived at, seems to help people. Narayan raises a deeply philosophical question here: if performing goodness produces actual good, does the performer’s motivation matter?

Chapter Five

Summary

The flashback resumes. Raju is at the height of his career as Railway Raju, the indispensable guide. He has developed a sophisticated network of relationships with local shopkeepers and hoteliers, earning commissions by directing tourists to them. He meets Marco — a dry, precise, scholarly man obsessed with cave paintings — and Rosie, his wife: beautiful, graceful, and immediately fascinating to Raju. He arranges their excursions, observes their strained relationship, and is increasingly drawn to Rosie, who reveals her background as a classical dancer from a devadasi family.

Commentary

The introduction of Marco and Rosie brings the novel’s central triangle into focus. Marco is drawn with deliberate flatness: he is intelligent but cold, devoted to his research to the exclusion of human warmth, incapable of seeing what is in front of him, which is his wife’s loneliness and his guide’s growing attraction. Raju, by contrast, sees Rosie very clearly. He recognises her talent, her frustration, and her hunger for someone who will value what her husband ignores. His attraction to her is not entirely cynical; there is something genuine in his appreciation of her art. But it is mixed, from the beginning, with self-interest — a combination that will characterise everything he does in relation to her.

Chapter Six

Summary

The present timeline. Seasons pass in the village — festivals, monsoons, harvests — and through all of them, Raju’s status as the village’s spiritual guide deepens. Then the drought comes. The river shrinks, crops fail, and the mood in the village turns anxious and desperate. Animals die. A fight breaks out over food. Raju, in response to the crisis, sends a message that the villagers interpret as a declaration that he will fast until rain comes.

Commentary

The drought is the pivot of the novel, the moment at which Raju’s comfortable imposture becomes genuinely dangerous. The drought functions on multiple levels simultaneously. Physically, it is a real crisis — the kind of agricultural disaster that devastated rural communities across India in the 1950s. Metaphorically, it mirrors the aridity of Raju’s spiritual life: the drought outside corresponds to the drought of genuine feeling within. The fast that Raju appears to have vowed represents the ultimate test of his performance: can he maintain the fiction to the point of self-destruction? And if he does, what does that make him?

Chapter Seven

Summary

The flashback deepens. Raju has become integrated into Marco and Rosie’s domestic life at Peak House, a bungalow near the caves. He manages their practical affairs while Marco conducts his research. He and Rosie grow close. She practises her classical dance, confides in him, and the intimacy between them gradually transforms into an affair. Marco is absent — not physically, but emotionally, absorbed entirely in his work. Raju feels conflicted but does not resist his attraction to Rosie.

Commentary

This chapter traces the moral deterioration of Raju’s original position. He came to Peak House as a hired guide; he has become something else entirely. Narayan handles the affair with considerable restraint — there is nothing sensational or melodramatic in the telling. The focus is on the emotional logic: Rosie is lonely, Raju is attentive, and in the gap between what Marco offers and what Raju offers, something inevitable happens. This restraint is itself a moral judgment: Narayan is not excusing what Raju does, but he is explaining it, which is the more difficult and more humane literary task.

Chapter Eight

Summary

Rosie reveals the full complexity of her background: she is from a devadasi family, a fact that carries both social stigma and artistic heritage. She married Marco partly to escape the constraints of her community, but the marriage has failed to provide her with what she truly needs — recognition of her art. Raju decides to become her promoter and manager. She begins to practise seriously, performing locally, and word of her talent spreads. Raju handles the finances, the bookings, and the practical logistics of her emerging career. He also, fatefully, forges her signature on documents relating to a jewellery box that Rosie has asked him not to touch.

Commentary

Chapter Eight marks Raju’s moral decline as irreversible. The forgery is a small act in practical terms, but it is enormously revealing psychologically. Up to this point, Raju has deceived others but has not stolen from them in any direct material sense. The forgery crosses a line: it is an act of betrayal toward the one person for whom he claims to feel genuine love. And it is motivated, ultimately, by the same impulse that has always driven him — the desire to manage, to control, to profit. Rosie’s story in this chapter also deserves careful attention. Her insistence on her dance, despite everything, is not simply stubbornness; it is the expression of a profound need to be valued for what she genuinely is rather than for her social position or her relationship to men.

Chapter Nine

Summary

Nalini — the name Raju has given Rosie for her public career — has become a star. She tours across India, performing to large and admiring audiences. Raju lives well, spending freely, indulging his taste for comfort and status. The relationship begins to show strain. The jewellery box becomes a point of crisis: the forgery is discovered, Marco provides testimony against Raju, and he is arrested.

Commentary

The collapse of Raju’s management of Rosie’s career is presented with the same ironic economy as its rise. Fame, Narayan suggests, does not change the fundamental character of those who pursue it; it only makes their flaws more visible. Raju’s extravagance, his arrogance, his inability to think beyond his immediate comfort — these are the qualities that brought him success in the short term and ruin in the long term. The role of Marco as the instrument of Raju’s exposure is also significant: the cold, scholarly man Raju dismissed as an obstacle turns out, in the end, to have the most power. This is another of Narayan‘s quiet ironies.

Chapter Ten

Summary

Raju is tried, found guilty, and sentenced to two years in prison. He adapts to prison life with the same pragmatic flexibility that has characterised his response to every environment he has encountered, finding a role for himself as a gardener and settling into the routine. He reflects on his life, but these reflections do not yet amount to genuine repentance. He is released and wanders, without purpose, until he finds himself at the temple by the Sarayu.

Commentary

The prison episode is brief but important. The reader might expect incarceration to be Raju’s moment of genuine transformation — the crucible in which the old self is broken down and a new self-forged. But Narayan refuses this easy narrative arc. Raju in prison is still Raju: adaptable, pragmatic, finding comfort where he can. His reflections are real, but they do not yet reach the depth of genuine change. This is honest. Real change, Narayan seems to suggest, is not produced by punishment alone. It requires something else — and it is only at the temple, under the pressure of the village’s faith and the approach of death, that Raju will find it.

Chapter Eleven

Summary

The present timeline reaches its culmination. Raju is fasting. The village has gathered around the temple in enormous numbers. He confesses his entire past to Velan, intending the confession as a release from his obligation. Velan hears it as a parable. The fast continues. Raju is weakening. The crowds swell. In the novel’s final pages, Raju walks to the river’s edge, performs ritual ablutions, prays with what feels like genuine sincerity, and collapses. The narrative tells us that he feels the rain —or perhaps dreams of it. Whether the rain actually comes, whether Raju lives or dies, the novel does not definitively say.

Commentary

The ending of The Guide is one of the most discussed and debated in modern Indian fiction, and rightly so. Narayan‘s ambiguity is not vagueness; it is a deliberate artistic and philosophical choice. If he had ended the novel with a clear miracle — Raju’s sincere prayer producing actual rain, Raju dying in a state of authenticated grace — the novel would have become a fable of religious faith. If he had ended it with clear evidence that Raju dies having changed nothing, the novel would have been a straightforward satire on credulity and fraud. By refusing both endings, Narayan holds the tension that the entire novel has been building: between performance and sincerity, between fraud and redemption, between what we appear to be and what we actually are.

Key takeaways (Part Five)

- Each chapter contributes a step in Raju’s movement from shop boy to “swami.”

- Past and present chapters constantly comment on each other.

- The novel’s moral questions arise from these structural juxtapositions.

Part Six: Narrative Structure and Technique

Key focus: How the novel is built, and why that matters.

The Five-Stage Arc

The Guide follows the classical five-stage narrative arc, though Narayan’s non-linear presentation complicates this somewhat.

The exposition establishes Raju at the temple, mistaken for a swami, and begins the long flashback that explains how he arrived there. The rising action encompasses Raju’s entire past: his career as Railway Raju, his affair with Rosie, his management of her career, and his growing moral compromise. The climax arrives with the forgery and imprisonment, which destroy the life he had built, and continues in the present with the drought and the declaration of the fast, which traps him in the most consequential performance of his life. The falling action consists of the fast itself: Raju’s genuine weakening, his confession to Velan, his gradual movement from performance to sincerity. The resolution — or anti-resolution — is the novel’s final scene, with its deliberate ambiguity about rain, death, and redemption.

Narrative Mode and Technique

One of the novel’s most technically interesting features is its management of narrative voice. The flashback sections are told in Raju’s own voice — first-person, self-justifying, charming, and unreliable. He is not a malicious liar, but he is a man who has spent his life telling people what they want to hear, including himself. Reading the flashback sections, students should remain alert to the gap between what Raju says and what Narayan implies. The present-day sections are told in a closer third-person, allowing more distance and irony.

The non-linear structure — the interweaving of past and present — serves several purposes. It creates suspense (we know Raju is in trouble before we know how he got there, which makes us read the flashback with a constant awareness of its consequences). It also creates irony: we see the past illuminated by our knowledge of its outcome, and the present by our knowledge of how it was produced.

Key takeaways

- The first-person flashback (Raju) vs. the third-person present (narrator) creates an unreliable but rich account.

- The five-stage arc is present, but scrambled through time.

- Suspense and irony arise from knowing Raju’s fate before knowing his full story.

Check your understanding

- Find one flashback moment where Raju’s account seems self-serving. What does Narayan’s irony suggest instead?

Part Seven: Genre, Mood, and Tone

Key focus: What kind of novel The Guide is, and how it feels to read it.

Type and Genre

The Guide is a novel of considerable generic complexity. On the surface, it belongs to the picaresque tradition (an episodic narrative about a resourceful, morally flexible protagonist who survives by his wits). But it also engages with the traditions of the bildungsroman (a novel of personal development) and the philosophical novel (which uses narrative to explore ideas about identity, responsibility, and transcendence). It is often described as a tragicomedy, and this label is apt: the novel is consistently funny and serious at once, a difficult balance Narayan maintains with characteristic ease. The Guide is also, in some sense, a spiritual novel — though of a very particular kind. It does not affirm any specific religious doctrine. It does not tell us that Raju’s fast is answered by God or that his death is martyrdom. What it does, with considerable subtlety, is raise the possibility that sincerity of intention, however belatedly arrived at, has a kind of transformative power — and it leaves us to decide what we make of that possibility.

Mood and Tone

Narayan‘s tone is one of his most distinctive literary qualities, and it rewards careful attention. He is ironic but never cruel. He is humorous but never trivialising. He writes about his characters with what can only be described as affectionate detachment: he sees their follies clearly and reports them faithfully, but he never loses sight of their humanity or their struggles. This tone is particularly important in relation to Raju, whose vices — vanity, dishonesty, self-indulgence — are consistently on display but who is never reduced to a caricature.

The novel’s mood shifts considerably throughout. The childhood flashback sections are warm and nostalgic, evoking a Malgudi of simple pleasures and manageable problems. The middle sections, dealing with Raju’s affair with Rosie and his management of her career, carry a more ambivalent tone: there is pleasure and excitement, but a growing unease as Raju’s choices become increasingly compromised. The prison sections are flat and resigned. The present-day sections shift from comfortable irony (Raju enjoying his swami role) to genuine tension (Raju trapped by his fast) to something approaching the philosophical sublime in the final pages.

Key takeaways

- The Guide blends picaresque, bildungsroman, tragicomedy, and spiritual exploration.

- Narayan’s tone combines humour with moral seriousness.

- Changing moods mirror Raju’s shifting circumstances and inner life.

Part Eight: Character Analysis

Key focus: How the main characters embody the novel’s questions.

Raju: The Protagonist

Raju is one of the most fully realised characters in Indian fiction in English, and part of what makes him so fascinating is the difficulty of arriving at a simple judgment about him. He is, by most objective measures, a bad person: he is dishonest, self-serving, vain, and finally a criminal. And yet he is also charming, genuinely perceptive, capable of real affection, and — in the end — apparently capable of genuine self-sacrifice.

The key to understanding Raju is to understand that his defining quality is adaptability. He does not have a fixed identity; he has a capacity to become whatever his environment requires. In the station shop, he becomes the indispensable assistant. As Railway Raju, he becomes the all-knowing guide. As Rosie’s manager, he becomes the entrepreneur. As the village swami, he becomes the holy man. In each of these roles, there is something genuine — his commercial instinct is real, his knowledge of Malgudi is real, his appreciation of Rosie’s talent is real, and his counsel to the villagers is often genuinely helpful. But in each role, the genuine element is mixed with self-interest, with performance, with the desire to be valued and rewarded.

What changes, in the final chapters, is not Raju’s adaptability but its direction. He can no longer adapt outward — can no longer find the angle that gets him out of his predicament. So he adapts inward: he turns the performance into a reality. Whether this is a genuine transformation or simply his most brilliant act is the question the novel leaves open.

Rosie / Nalini

Rosie is, in some ways, the novel’s moral centre — the character whose desires are most clearly legitimate and whose treatment most clearly indicts the men around her. She is from a devadasi family: she was born into a tradition that combines artistic accomplishment with social vulnerability, and she has experienced both. Her marriage to Marco was an attempt to escape the constraints of her community and achieve social respectability, but it has trapped her in a different way: as a woman married to a man who has no interest in her as a person and sees her primarily as a domestic convenience.

What Rosie wants — and what Raju, initially, genuinely provides — is recognition. She wants someone to see her dance and understand what it means: not just its technical accomplishment, but its emotional and spiritual significance. Raju does see this, and his encouragement of her career is one of the most sympathetic things he does in the novel. But his encouragement is never entirely disinterested: he manages her career because it brings him money and status, and when those interests conflict with hers (as they do, decisively, in the forgery episode), self-interest wins.

Rosie’s fate after Raju’s imprisonment is not shown to us directly, and this omission is significant in itself. She disappears from the narrative — as women in novels so often do once the men who have defined their stories are removed from the scene.

Marco

Marco — whose full name is never given, which is itself a mark of his function in the novel as a type rather than a full individual — is Raju’s foil and, in a sense, his nemesis. He is intelligent, rigorous, and entirely absorbed in his scholarship. He is incapable of ordinary human warmth and shows no interest in his wife’s emotional life. He is not cruel to Rosie in any active sense; he simply does not see her, which is its own form of cruelty.

Marco’s role in providing the evidence that convicts Raju is the novel’s sharpest irony regarding his character. Throughout the novel, he has been presented as someone who misses what is directly in front of him. Yet in the end, he sees Raju’s crime clearly and acts on it with precision. The cold man of scholarship turns out to be more observant and more decisive than the charming man of instinct. This is Narayan‘s most cutting judgment on Raju: not that he was outsmarted by a clever rival, but that he was undone by a man he had underestimated and, perhaps, wronged.

Velan

Velan is one of Narayan’s most carefully drawn minor characters. He is the representative of the village’s faith — not blind faith in the pejorative sense, but genuine, deeply rooted trust that wisdom and holiness can exist in the world and are worth seeking out. His misreading of Raju is not stupidity; it is a form of hope. He needs Raju to be what he appears to be, and he interprets everything Raju does in light of that need.

The scene in which Raju confesses his entire past to Velan, expecting to be released from his obligation, and finds instead that Velan hears the confession as a parable of spiritual struggle, is one of the most brilliantly comic and most deeply moving scenes in the novel. It is comic because of the perfect misunderstanding; it is moving because of what it reveals about the nature of faith and the impossibility of disillusionment when belief is sufficiently deep.

Key takeaways

- Raju’s adaptability is both his strength and his moral weakness.

- Rosie exposes gendered limits on artistic freedom.

- Marco and Velan act as foils, revealing different kinds of “vision” and belief.

Part Nine: Key Themes

Key focus: The main ideas you should be able to discuss in essays.

Identity and Performance

The novel’s central preoccupation is with the relationship between identity and performance. Raju is, in every phase of his life, performing a role: the dutiful shopkeeper’s son, the worldly-wise guide, the devoted manager, the holy swami. The question the novel asks is whether there is any self beneath these performances — any essential Raju that exists independently of what he is performing in any given moment.

Narayan does not give a confident answer to this question. But the final chapters suggest that performance, taken to its limits, can become reality: that a man who performs sincerity long enough may find that it has, in some sense, become real. This is a philosophically interesting and morally complex idea that rewards careful thought.

Deception and Self-Deception

Raju deceives others, but he also deceives himself. His narrative of his relationship with Rosie, of his management of her career, of his reasons for the forgery — all of these are shaped by self-justification. He tells his story in a way that flatters himself most. But Narayan’s irony allows us to see through the self-justification to the more uncomfortable truth. Raju’s self-deception is not simply a moral failing; it is a human universal, and Narayan treats it with the compassion it deserves.

Gender and Artistic Freedom

Rosie’s story raises questions that are as relevant today as they were in 1958. She is a woman of genuine artistic talent whose ability to express and develop that talent is entirely dependent on the men around her: first Marco, whose indifference denies her the emotional context she needs; then Raju, whose support is genuine but compromised by self-interest. Her career as Nalini is both a triumph and a form of dependence. The novel does not fully resolve the tension between Rosie’s achievement and the conditions under which it was achieved, and that lack of resolution is one of its most honest qualities.

Fate, Circumstance, and Agency

One of the novel’s persistent questions is how much Raju is responsible for his own life. To what extent did he choose the path he followed, and to what extent was he chosen by circumstance? The railway came to Malgudi; Marco and Rosie stopped at his father’s station. These are not things Raju chose. But he chose how to respond to them — or did he? Narayan‘s novel is genuinely uncertain about the balance between fate and agency, and this uncertainty is part of what makes it a serious work of literature rather than a simple moral tale.

Redemption and Transformation

The question of whether Raju is redeemed — whether his final fast represents genuine spiritual transformation — is the question that the novel most insistently raises and most carefully refuses to answer. The novel’s power lies precisely in holding the question open.

Key takeaways

- You should be able to trace identity/performance, deception, gender, fate, and redemption through key scenes.

- The themes are interlinked: e.g., performance is tied to gender (Rosie) and to redemption (Raju’s fast).

- Ambiguity is not a weakness but a deliberate strategy.

Conclusion: Why The Guide Still Matters

Key focus: How to connect your reading to larger questions.

It is tempting, when studying a canonical text, to treat it as a monument: something to be admired from a respectful distance, its meanings fixed and its significance established. The Guide resists this treatment. It is, at its core, a deeply personal and irreducibly human novel, and its concerns — with who we are versus who we appear to be, with the possibility of change, with the strange relationship between performance and sincerity — are as pressing in the twenty-first century as they were when Narayan wrote it.

Raju is not a hero in any conventional sense. He is not brave, not principled, not particularly self-aware until very late in his story. But he is unmistakably human — recognisable in his self-serving logic, his genuine affections, his capacity for self-deception, and his eventual, tentative reaching toward something better than he has been. If we are honest, we see something of ourselves in him: not our worst selves, perhaps, but our most complicated selves — the selves we perform when we are not sure what we actually are.

Narayan’s genius is to have made this recognition possible without making it comfortable. The Guide does not let us off the hook. Its irony is pointed, its moral intelligence is precise, and its ending — with its haunting refusal to confirm or deny Raju’s redemption — leaves us to sit with the discomfort of uncertainty. In a literary culture that often prefers resolution, this is a rare and valuable quality.

The Guide offers something that the very best literature always offers: not answers, but better questions. It asks us to think carefully about the stories we tell about ourselves, about the roles society assigns us and the roles we accept, about the relationship between appearance and reality, between intention and consequence, between the life we live and the life we might have lived. These are not merely academic questions. There are questions about how to be human — and that is precisely why a novel written in 1958, set in a fictional small town in South India, continues to speak to readers everywhere, with undiminished clarity and undiminished force.

Approach The Guide with patience, with close attention, and with a willingness to sit with questions that do not resolve easily. Do that, and you will find that Narayan‘s Malgudi is not merely a place you have studied — it is a place you have, in some sense, lived in.