Introduction-

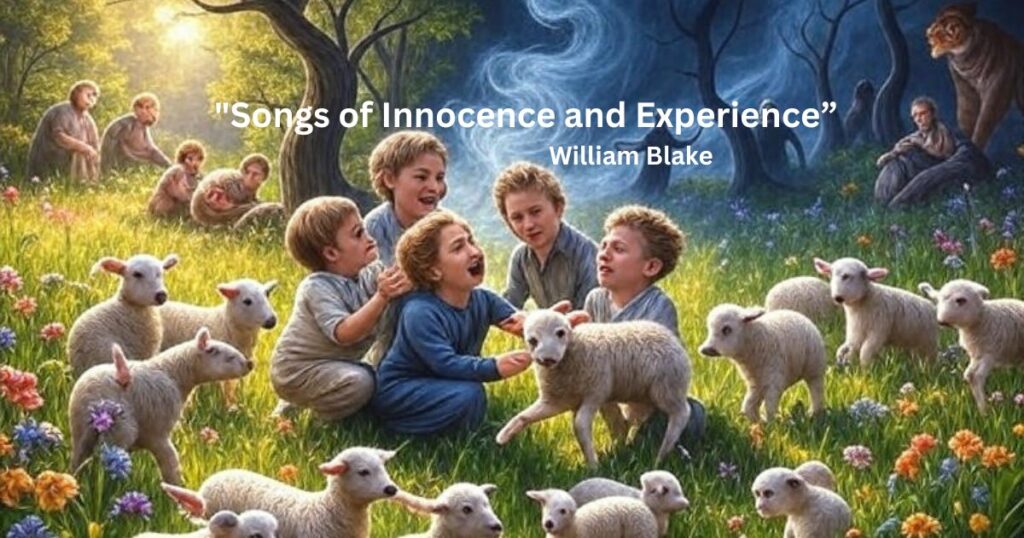

William Blake (1757-1827) was an English poet, painter, engraver, and visionary who saw the world differently from most. Born in London to a working-class family with nonconformist religious beliefs, Blake showed remarkable artistic talent from an early age. At fourteen, he became an engraver’s apprentice, later studying at the Royal Academy.

During his lifetime, few people recognized Blake’s genius. He self-published his works as illuminated manuscripts, combining his poetry with hand-colored engravings—a revolutionary artistic form. The French and American Revolutions deeply influenced his thinking, as did mysticism and radical politics. Blake fearlessly criticized industrialization, social injustice, church hypocrisy, and oppressive institutions.

His masterpieces, Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), explore profound themes: innocence, experience, divinity, and human suffering. These works blend Romantic ideals with prophetic vision. Though Blake died in poverty, his impact on later literature and art has been immeasurable.

“Songs of Innocence” Poems

Name of the Poem: “Introduction”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: A piper plays joyful songs while walking through wild valleys.

- Lines 3-4: He encounters a child sitting on a cloud, laughing and speaking to him.

- Lines 5-6: The child asks for a song about a Lamb, which the piper plays cheerfully.

- Lines 7-8: The child requests the song again, and when the piper plays it, the child weeps.

- Lines 9-10: The child tells the piper to put down his pipe and sing the songs instead.

- Lines 11-12: The piper sings, and the child weeps with joy.

- Lines 13-14: The child asks the piper to write these songs in a book so everyone can read them.

- Lines 15-16: The child vanishes, and the piper picks a hollow reed.

- Lines 17-20: He fashions a pen from the reed, makes ink from stained water, and writes his happy songs for every child to enjoy.

Gist of the Poem

The poem tells the story of a piper who meets a visionary child that inspires him to create joyful music celebrating innocence. The child’s requests progress from piping to singing to writing, symbolizing how artistic expression evolves and becomes permanent. The piper transforms natural, spontaneous joy into accessible art that can be shared. When the child vanishes, representing fleeting inspiration, the piper preserves this moment by writing it down. The poem introduces the entire collection by emphasizing childlike wonder and the importance of sharing innocent happiness with the world.

Critical Analysis

The “Introduction” to Songs of Innocence serves as a pastoral invocation, setting the stage for a celebration of childlike purity and divine inspiration. The piper represents the poet-artist, while the child on a cloud embodies innocence itself and serves as a muse-like guide. This ethereal vision reflects Blake’s profound belief that imagination serves as a bridge to spiritual truth, standing in stark contrast to the rational thinking of the Enlightenment era.

The progression from piping (instinctual, spontaneous art) to singing (emotional expression) to writing (permanent record) mirrors how creativity evolves. It suggests that art’s ultimate purpose is to democratize joy, making it available to “every child”—meaning all people who retain their capacity for wonder. The child’s tears blend joy and sorrow, hinting at innocence’s fragility, a theme Blake explores throughout both collections.

Blake critiques societal corruption by idealizing a pre-industrial, harmonious world where nature and childhood align with divine harmony. The rural pen made from a reed and the clear water used for ink symbolize uncorrupted creation, standing in opposition to the urban decay Blake depicts in later works. His illuminated style, which integrates text and image, enhances the poem’s visionary quality and invites readers into an innocent state before experience intrudes.

This opening poem prepares us for the collection’s exploration of untainted human potential, positioning poetry as salvation from worldly corruption. It embodies Blake’s Romantic philosophy, which values intuition over reason and sees childhood as a divine archetype worthy of reverence.

Name of the poem: “The Lamb”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: The speaker addresses a little lamb, asking who created it.

- Lines 3-4: Who gave it life and lets it feed by streams and meadows?

- Lines 5-6: Who gave it soft, woolly clothing that brings delight?

- Lines 7-8: Who gave it such a tender voice that fills the valleys with joy?

- Lines 9-10: The question is repeated: Little Lamb, who made you?

- Lines 11-12: The speaker offers to tell the lamb the answer.

- Lines 13-14: The creator is called by the lamb’s name, as He calls Himself a Lamb.

- Lines 15-16: He is meek and mild, and He became a little child.

- Lines 17-18: The speaker identifies as a child, and the lamb as a child too—all called by His name.

- Lines 19-20: The speaker blesses the lamb with God’s protection, repeating the blessing for emphasis.

Gist of the Poem

A childlike speaker asks a gentle lamb about its creator, marveling at its soft features and joyful voice. The questions highlight the lamb’s innocence and divine design. The speaker then reveals that God, who embodies meekness as the Lamb of God (Jesus Christ), made the lamb. This creates a beautiful connection between the creator, the child, and the lamb—all sharing in divinity. The poem concludes with blessings, affirming God’s loving, benevolent care for all creatures.

Critical Analysis

“The Lamb” perfectly captures Blake’s portrayal of innocence as a harmonious union with divinity. The poem’s structure resembles a catechism—questions followed by affirming answers—which mirrors how children learn and emphasizes the simplicity of faith. The lamb symbolizes Christ (the Lamb of God), innocence, and vulnerability. Its “softest clothing” and “tender voice” evoke pastoral purity, standing in sharp contrast to industrial harshness.

Blake challenges rationalism by prioritizing intuitive wonder. The child’s voice represents uncorrupted perception, and there’s a beautiful reciprocity in naming: “He is called by thy name.” This underscores Blake’s mystical belief that God becomes childlike, which inverts traditional religious hierarchies. In Blake’s illuminated plates, the lamb’s image reinforces this tenderness, inviting empathetic reading.

The repetition creates a hymn-like rhythm that blends joy and reverence. Yet it subtly foreshadows experience’s shadows—particularly in its counterpart poem, “The Tyger.” The poem affirms Christian compassion while subtly protesting societal exploitation. Blake portrays innocence as a divine entitlement that is threatened by worldly corruption. His deceptively simple language masks profound theology, celebrating creation’s benevolence and urging readers to reclaim childlike faith amid worldly struggles.

Name of the Poem: “The Chimney Sweeper”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: The speaker’s mother died when he was young, and his father sold him into chimney sweeping before he could properly speak.

- Lines 3-4: He sweeps chimneys and sleeps covered in soot, crying “‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep!”—his childish attempt to say “sweep.”

- Lines 5-6: Little Tom Dacre cries when his curly, lamb-like hair is shaved off.

- Lines 7-8: The speaker comforts him, saying his bare head will prevent soot from spoiling his white hair.

- Lines 9-10: Tom quiets down, and that night, he has a vivid dream.

- Lines 11-12: In the dream, thousands of sweepers are locked in black coffins.

- Lines 13-14: An angel appears with a key and frees them all.

- Lines 15-16: They run, laugh, wash in a river, and shine in the sun on a green plain.

- Lines 17-18: Naked and free, they leave their bags behind and rise on clouds, playing in the wind.

- Lines 19-20: The angel tells Tom: “If you’re a good boy, God will be your father, and you’ll never lack joy.”

- Lines 21-22: Tom wakes up, and they rise in the dark to work with their bags and brushes.

- Lines 23-24: Though it’s cold, Tom is happy because he believes doing his duty will keep him from harm.

Gist of the Poem

A young chimney sweeper recounts his tragic entry into child labor after losing his mother and being sold by his father. He comforts another boy, Tom Dacre, who dreams of angelic liberation from their coffin-like confinement. The dream promises freedom, joy, and divine fatherhood through being good. When they wake, they return to their harsh work, but Tom finds comfort in hope. The poem contrasts grim reality with a visionary escape.

Critical Analysis

“The Chimney Sweeper” from Songs of Innocence offers a subtle but powerful indictment of child labor and institutional hypocrisy, all delivered through a child’s naive optimism. The speaker’s matter-of-fact tone actually makes the horror more striking—he was sold into slavery and sleeps in soot—highlighting how society had normalized this exploitation during industrialization.

Tom’s dream, with its coffins symbolizing chimneys and a death-like existence, offers religious consolation. However, Blake critiques this as false hope that actually perpetuates oppression. The angel’s advice to “be a good boy” implies that duty excuses suffering—a dangerous message. The lamb imagery of Tom’s curly hair evokes sacrificed innocence, linking to Christian sacrifice while protesting the church’s complicity in poverty.

The poem’s irony lies in the boys’ resilient faith despite their cruel treatment, which urges readers to question pious platitudes that ignore the need for actual reform. Blake’s illuminated plates often show ethereal release, contrasting with the verbal realism and creating a dual reading: surface salvation versus underlying critique.

Compared to the Experience version of this poem, we see innocence’s self-deception, where hope blinds children to systemic evil. Blake ultimately advocates for social change, portraying childhood as divine yet corrupted by greed, and calling for compassionate action rather than passive piety.

Name of The poem: “The Nurse’s Song”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: Children’s voices and laughter echo across the green and up the hill.

- Lines 3-4: The nurse’s heart rests peacefully; everything is still.

- Lines 5-6: She calls them home as the sun sets and dew begins to rise.

- Lines 7-8: She urges them to leave their play until morning light.

- Lines 9-10: The children refuse, pointing out it’s still light and they can’t sleep yet.

- Lines 11-12: Birds still fly in the sky, and the hills are covered with sheep.

- Lines 13-14: The nurse agrees to let them play until the light fades, then they must go to bed.

- Lines 15-16: The children leap, shout, and laugh joyfully; the hills echo with their voices.

Gist of the Poem

A nurse watches children play joyfully on a green hill. As sunset approaches, she calls them in for safety and rest. The children plead to continue playing, noting the lingering daylight and nature’s activity. The nurse kindly relents, granting them more time. Their exuberant response echoes through the landscape, symbolizing harmonious freedom between generations and nature.

Critical Analysis

“Nurse’s Song” from Innocence celebrates childhood’s boundless energy and adult benevolence, portraying an ideal harmony between generations and the natural world. The nurse’s initially restful heart reflects genuine empathy. Her call home is protective rather than authoritarian—a sharp contrast to the resentful nurse in the Experience version.

The children’s voices on the “green” symbolize uncorrupted vitality, with the echoing hills amplifying their communal joy and evoking a pre-industrial idyll. Blake critiques rigid structures by showing flexible authority. The nurse’s concession affirms that play is essential to innocence, aligning with the Romantic movement’s valuation of childhood freedom.

The repetition and simple rhyme scheme mimic playful rhythm, inviting readers to immerse themselves in this Edenic state. Yet there’s subtle tension—the “dews of night” hint at encroaching darkness, foreshadowing experience’s inevitable loss of innocence. Blake’s illuminated plates often depict vibrant outdoor scenes, reinforcing this visual harmony.

The poem protests child repression, advocating nurturing over control, while exposing societal threats to such purity. Blake’s vision urges us to reclaim innocent joy against oppressive norms that would restrict childhood’s natural freedom.

Name of the Poem: “Holy Thursday”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: On Holy Thursday, innocent children with clean faces walk in pairs, wearing red, blue, and green.

- Lines 3-4: Grey-headed beadles lead them with white wands as they flow like the River Thames into St. Paul’s Cathedral dome.

- Lines 5-6: They appear as a multitude, like harmonious flowers of London town.

- Lines 7-8: Seated in companies, they raise their hands like a mighty wind.

- Lines 9-10: Below them sit the wise guardians of the poor.

- Lines 11-12: The poem warns: cherish pity, lest you drive away an angel. The children’s song sounds like harmonious thunder.

Gist of the Poem

Orphaned charity children parade into St. Paul’s Cathedral on Holy Thursday, organized and colorful in their uniforms. Led by beadles, they flow like a river, symbolizing unity. Once seated, they sing praises to God, evoking natural harmony. Guardians watch benevolently from below. The poem urges genuine charity to welcome divine presence.

Critical Analysis

“Holy Thursday” from Innocence presents what seems like an idyllic charity parade, but Blake subtly critiques institutional hypocrisy and poverty’s persistence. The children’s “innocent faces clean” and colorful attire mask underlying exploitation. Their regimented march in pairs suggests control rather than freedom.

Blake’s river simile implies overwhelming numbers resulting from societal neglect, flowing into the church as if it offers salvation. The “harmonious thunderings” of their song blend awe and power, but the “wise guardians” are presented ironically—they profit from pity without enacting real reform. The plea to “cherish pity” exposes superficial charity, urging true compassion to avoid divine rejection.

Blake’s illuminated plates show vibrant processions, contrasting with the verbal ambiguity and inviting dual interpretation: Is this celebration or indictment? Compared to the Experience version, this poem reveals innocence’s blindness to systemic failure. Blake protests against Enlightenment claims of progress, highlighting poverty’s persistence amid wealth, and advocating for radical empathy rather than token charity.

“Songs of Experience” Poems

Name of the Poem: “Introduction”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: The Holy Word calls to the lapsed, fallen Soul.

- Lines 3-4: It weeps over the ancient, starry ways of heaven.

- Lines 5-6: The Bard, who knows past, present, and future, calls to Earth.

- Lines 7-8: “O Earth, O Earth, return! Arise from the dewy grass!”

- Lines 9-10: Night is worn away; the starry floor and watery shore are given to you.

- Lines 11-12: Until the break of morning light appears.

Gist of the Poem

A prophetic Bard summons Earth from spiritual slumber, invoking the divine call to the fallen soul. The Holy Word weeps for lost harmony. The Bard’s wisdom spans all time, urgently calling for awakening. As night fades, revealing starry and watery realms, dawn promises spiritual renewal.

Critical Analysis

The “Introduction” to Songs of Experience shifts dramatically to a prophetic tone, contrasting sharply with Innocence‘s pastoral joy. Here we encounter fallen humanity’s lament. The Bard serves as Blake’s alter ego, calling to Earth—which symbolizes materiality and oppression—to awaken from spiritual slumber. This critiques rationalism’s chains on the human spirit.

The “Holy Word” evokes biblical creation, but its weeping highlights post-lapsarian (after the Fall) despair, urging humanity to reclaim divine vision. The “starry pole” and “watery shore” represent Urizen’s tyrannical reason and emotional turbulence in Blake’s mythology, given temporary dominion until dawn brings liberation.

Blake’s mysticism sees experience as corrupted innocence, but he calls for imaginative revolt against institutional religion and oppressive society. The poem’s imperative rhythm demands action, foreshadowing the collection’s exposure of suffering. In illuminated form, it integrates cosmic imagery, enhancing its apocalyptic urgency.

Critically, this poem frames experience as necessary for transcendence, blending hope with critique. We cannot return to innocence, but we can move forward to a higher synthesis.

Name of the Poem: “The Tyger”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: Tyger, tyger, burning bright in the forests of the night.

- Lines 3-4: What immortal hand or eye could frame your fearful symmetry?

- Lines 5-6: In what distant deeps or skies did the fire of your eyes burn?

- Lines 7-8: On what wings did he dare to aspire? What hand dared seize that fire?

- Lines 9-10: What shoulder, what art could twist the sinews of your heart?

- Lines 11-12: When your heart began to beat, what dread hand? What dread feet?

- Lines 13-14: What hammer, what chain? In what furnace was your brain forged?

- Lines 15-16: What anvil? What grasp dared hold such deadly terrors?

- Lines 17-18: When the stars threw down their spears and watered heaven with their tears…

- Lines 19-20: Did he smile at his work? Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

- Lines 21-24: The opening stanza’s question is repeated.

Gist of the Poem

The speaker marvels at the tyger’s fierce beauty, questioning what creator could forge such a terrifying yet symmetrical creature. Imagery of fire, forges, and cosmic rebellion evokes both awe and terror. The poem contrasts the tyger’s ferocity with the lamb’s meekness. The central unanswered question probes divine duality: Could the same God create both? The repetition emphasizes the enduring mystery.

Critical Analysis

“The Tyger” interrogates creation’s duality, juxtaposing terror and beauty to challenge simplistic notions of a benevolent divinity. The tyger’s “fearful symmetry” and “fire” eyes symbolize revolutionary energy and destructive force. The industrial imagery—hammers, chains, furnaces, anvils—mirrors Blake’s era of industrialization, suggesting creation as violent forging rather than gentle molding.

The rhetorical questions—”What the hammer? What the chain?”—evoke Promethean crafting, implying a distant, perhaps even malevolent creator. This contrasts starkly with Innocence‘s gentle God. The pivotal question, “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” highlights Blake’s philosophy of contraries: innocence versus experience, lamb’s meekness versus tyger’s ferocity, embodying his dialectic approach to understanding reality.

The stars throwing down their spears and watering heaven with tears suggests cosmic rebellion, possibly alluding to Satan’s fall or even the French Revolution. Blake critiques tyrannical order while acknowledging revolutionary violence. The trochaic rhythm hammers like metalwork, amplifying urgency, while the illuminated tyger images convey sublime terror.

Critically, the poem rejects simplistic theology, positing experience as essential for understanding divinity’s complexity, where creation encompasses both good and evil. Unlike “The Lamb,” this poem leaves awe unresolved, urging imaginative engagement with mystery. Blake protests passive faith, advocating for visionary perception that can reconcile opposites rather than deny them.

Name of the Poem: “The Chimney Sweeper”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: “A little black thing” cries “‘weep! ‘weep!” in the snow.

- Lines 3-4: The speaker asks where his parents are.

- Lines 5-6: “They are both gone up to the church to pray,” having sold him into sweeping.

- Lines 7-8: “Because I was happy upon the heath, and smiled among the winter’s snow, they clothed me in the clothes of death.”

- Lines 9-10: They taught me to sing the notes of woe while praising “God & his Priest & King.”

- Lines 11-12: “Who make up a heaven of our misery.”

Gist of the Poem

A soot-covered chimney sweeper cries in the cold snow. When questioned, he reveals his parents are at church—the same parents who sold him into this brutal labor. He once knew happiness, but his parents dressed him in “the clothes of death” and taught him to mask his suffering with praise for God. Society and religion work together to make “a heaven of our misery,” justifying exploitation through piety.

Critical Analysis

“The Chimney Sweeper” from Experience powerfully exposes religion and society’s complicity in child exploitation. This version contrasts sharply with Innocence‘s hopeful dream, presenting instead bitter, unvarnished reality.

The “little black thing” dehumanizes the child, reducing him to an object. His cry of “‘weep! ‘weep!” echoes through wintry desolation, symbolizing forsaken innocence. The parents’ church attendance indicts hypocritical piety—they literally “clothed me in the clothes of death” and use God to justify their abandonment.

The sweeper’s bitter recognition that he was “happy upon the heath” before this exploitation shows the loss of natural childhood joy. The ironic “praise” reveals indoctrination, where institutional religion makes misery seem like “heaven.” Blake critiques the church as an opiate perpetuating inequality rather than addressing it.

Blake’s sparse structure amplifies the accusation. There’s no dream escape here—only stark condemnation of poverty, exploitation, and false religion. The illuminated plates show isolated figures, heightening the pathos. Unlike Innocence‘s resilient hope, Experience unmasks deception, urgently calling for reform. Blake protests industrial capitalism’s devastating toll on the most vulnerable members of society.

Name of the Poem: “The Nurse’s Song”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: When the voices of children are heard on the green, the nurse’s heart turns sick.

- Lines 3-4: Whisperings are heard in the dale, around deserted play areas.

- Lines 5-6: The nurse’s face turns green and pale when she recalls her own youth.

- Lines 7-8: Her days of youth were wasted in disguise.

- Lines 9-10: Her spring and her day were wasted in play.

- Lines 11-12: Her winter and night were spent in disguise, and now her life will come in sighs.

Gist of the Poem

Children’s playful voices evoke not joy but sickness and envy in the nurse. Their happiness triggers bitter memories. She laments what she sees as wasted youth spent in play. Play now seems futile against the reality of aging and regret. Experience has tainted joy with melancholy and resentment.

Critical Analysis

“Nurse’s Song” from Experience completely inverts Innocence‘s harmony, portraying adulthood’s bitterness toward childhood freedom. The nurse’s “heart is sick” at the echoes of children’s play. Her “green and pale” face symbolizes both jealousy and physical decay, critiquing experience’s loss of vitality.

The repeated word “wasted” reflects repressive social norms that stifled her natural joy, contrasting sharply with Innocence‘s permissive, caring nurse. Blake exposes how societal corruption makes innocence seem like mere “disguise,” reducing life to “sighs”—resignation and regret.

The rhythm’s somber flow mirrors this resignation. The illuminated scenes are likely shadowed and melancholic. Blake critiques restrictive gender roles and social expectations, with the nurse embodying thwarted desire and lost potential.

This poem urges readers to resist experience’s cynicism and reclaim innocence’s capacity for joy before it’s too late.

Name of the Poem: “Holy Thursday”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: Is this a holy thing to see in a rich and fruitful land, babies reduced to misery?

- Lines 3-4: Fed with a cold and usurous (greedy, exploitative) hand?

- Lines 5-6: Is a trembling cry a song of joy?

- Lines 7-8: Can it be a song of joy? And so many children poor, like lambs among eternal thorny winter.

- Lines 9-10: It is a land where the sun never shines, and the fields are bleak and bare.

- Lines 11-12: Wherever the sun does shine, and wherever rain does fall, babies should never hunger there, nor poverty bring them to misery. Such things would not happen if we loved as we should.

Gist of the Poem

The poem questions how charity can exist in a prosperous land while children suffer in misery. Children fed coldly and exploitatively cannot truly sing songs of “joy”—their cries are trembling with fear and suffering. Lamb-like innocents endure a thorny, eternal winter. England has become a land where sun never shines and fields lie barren. True bounty requires both sunshine and rain. Poverty is unnecessary and unnatural in a truly benevolent world that practices genuine love.

Critical Analysis

“Holy Thursday” from Experience completely dismantles Innocence‘s facade, indicting hypocritical charity and societal failure with righteous anger. The rhetorical questions expose bitter irony: How can we see “babes reduced to misery” in a “rich and fruitful land”? How can we feed them with a “cold and usurous hand”—exploiting even in charity?

The “trembling cry” mocks the pious songs from the Innocence version. These children are not joyfully singing; they’re trembling. The “lambs” among “thorns” symbolizes crucified innocence—children sacrificed on the altar of social and economic inequality. “Eternal winter” evokes spiritually barren England, contrasting with the potential paradise it could be.

Blake demands reform, asserting poverty’s unnaturalness wherever “sun does shine” and “rain does fall”—meaning everywhere. The poem’s structure, built on increasingly outraged questions, creates emotional momentum. The illuminated contrasts are likely stark and vivid.

This poem protests both church and state’s complicity in maintaining inequality. Blake insists that genuine love and compassion would eliminate such suffering, making it clear that poverty amid plenty is a moral failure, not an inevitable condition.

Name of the Poem: “London”

Line-by-Line Summary

- Lines 1-2: The speaker wanders through chartered streets, near the chartered Thames River.

- Lines 3-4: In every face he meets, he marks signs of weakness and woe.

- Lines 5-6: In every cry of every man, in every infant’s cry of fear, in every voice, in every ban—he hears mind-forged manacles.

- Lines 7-8: The chimney-sweeper’s cry appalls (blackens) every church.

- Lines 9-10: The hapless soldier’s sigh runs in blood down palace walls.

- Lines 11-12: Most of all, through midnight streets he hears the youthful harlot’s curse that blasts the newborn infant’s tear and plagues the marriage hearse with disease.

Gist of the Poem

The speaker observes London’s oppressed, commercialized streets and even its chartered river. Every face shows suffering. Every cry reveals mental chains forged by ideology. Institutions are blackened by the exploitation they ignore: The chimney-sweeper’s cry condemns the church; the dying soldier’s blood stains the palace. The cycle of misery corrupts everything—prostitution, disease, birth, and marriage become intertwined in death.

Critical Analysis

“London” offers one of Blake’s most vivid condemnations of urban decay and institutional oppression, portraying a city trapped in endless cycles of suffering. “Chartered” streets and Thames symbolize commodified freedom—even nature is bought and sold under capitalism’s control.

“Marks of weakness, marks of woe” universalizes despair across all social classes. Blake’s phrase “mind-forged manacles” has become famous—these are mental chains, ideological bondage created by church, state, and commerce, more powerful than physical restraints because people internalize them.

The chimney-sweeper’s cry “appalls” (blackens and horrifies) the church, exposing its hypocrisy in tolerating child exploitation. The soldier’s blood staining palace walls indicts those in power who send young men to die. The harlot’s curse “plagues marriage hearse”—linking prostitution, venereal disease, and family corruption in a devastating image where marriage becomes death.

The ABAB rhyme scheme and iambic tetrameter create a relentless march, mirroring the entrapment Blake describes. His prophetic vision demands awakening from apathy. The poem critiques Enlightenment promises of progress while highlighting Revolutionary-era inequalities that persist.

“London” encapsulates Experience‘s totality—a world where “mind-forged manacles” bind everyone, and innocence’s hope seems impossibly distant.

Comprehensive Critical Analysis: Comparing the Two States of Human Life

William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience present two contrary states of the human soul: innocence as untainted, harmonious existence, and experience as corrupted, oppressive reality. Innocence portrays childhood’s divine purity, nature’s benevolence, and intuitive faith. Experience reveals societal institutions’ tyranny, the loss of joy, and spiritual alienation. This dialectic forms the heart of Blake’s philosophy—contraries are essential for progression. He critiques Enlightenment rationalism and industrial society’s dehumanization. The paired poems in these collections amplify contrasts, exposing how innocence yields to experience through corruption.

The Transformation of Vision: The “Introduction” Poems

The two “Introduction” poems perfectly exemplify this shift. In Innocence, a piper joyfully creates music for children, symbolizing art’s innocent origins in divine inspiration. The encounter with the child on a cloud feels effortless, natural, blessed. In Experience, a Bard prophetically summons fallen Earth, lamenting lost harmony and urgently calling for awakening from material bondage. We move from pastoral glee to apocalyptic summons, illustrating the soul’s descent from grace.

The Exploitation of Childhood: “The Chimney Sweeper”

The two “Chimney Sweeper” poems offer perhaps the starkest contrast. Innocence provides dream-escape and pious hope. Tom’s vision promises angelic freedom, creating comfort—but Blake subtly critiques this comfort as false consolation that allows exploitation to continue. In Experience, the mask drops entirely. The sweeper’s parents use religion to justify selling their child, literally building “a heaven of our misery.” Innocence’s resilience becomes experience’s bitter resignation. Blake protests child labor’s institutionalization, showing how religion and economic systems work together to exploit the vulnerable.

The Loss of Joy: “Nurse’s Song”

“Nurse’s Song” inverts generational harmony completely. In Innocence, we see empathetic allowance of play, echoing nature’s vitality and seasonal rhythms. The nurse delights in children’s joy. In Experience, the nurse actively envies them, viewing youth as “wasted,” her sickness reflecting repressed desires and societal constraints. This highlights how experience’s cynicism erodes innocent joy, turning what should be nurturing care into bitter resentment.

The Hypocrisy of Charity: “Holy Thursday”

“Holy Thursday” exposes charity’s facade. Innocence depicts an orderly parade that appears harmonious, yet the regimentation suggests control rather than freedom. Experience directly questions this: How can misery exist in abundance? Why are children hungry in a fruitful land? Blake deems poverty unnatural and unnecessary. Innocence’s piety becomes experience’s indictment of false benevolence that maintains inequality while appearing charitable.

The Duality of Creation: “The Lamb” and “The Tyger”

Beyond the paired poems, “The Lamb” and “The Tyger” contrast different facets of creation. The lamb’s gentle maker affirms a benevolent God of love and meekness. The tyger’s fierce forging questions whether the same creator could craft such terror, embodying experience’s confrontation with violence, revolution, and destructive power. Can the same hand create both? Blake refuses easy answers.

From Birth to Bondage: “Infant Joy” and “Infant Sorrow”

“Infant Joy” celebrates birth’s purity—a two-day-old child brings happiness simply by existing. “Infant Sorrow” depicts entry into a “dangerous world” filled with strife, where the infant struggles and is immediately bound in swaddling clothes, symbolizing society’s constraints from the very moment of birth.

The Destruction of Natural Joy: “The Echoing Green” and “The Garden of Love”

“The Echoing Green” evokes communal play that naturally fades with age and the day’s progression, but without bitterness—it’s the natural cycle of life. “The Garden of Love,” however, shows joy forcibly destroyed. Where the speaker once played on the green, priests have built a chapel, binding with briars his “joys and desires.” The garden has become a graveyard. Natural pleasure has been replaced with institutional restriction and death.

The Total Vision: “London”

“London” encapsulates experience’s totality in concentrated form. The “mind-forged manacles” bind all citizens—chimney sweepers, soldiers, prostitutes, families. There’s no counterpart in Innocence because innocence cannot conceive of such total corruption. This poem represents Blake’s prophetic vision at its most devastating, showing a society where every institution has failed, where even mental freedom has been chained.

Blake’s Dialectical Philosophy

Blake’s vision goes beyond simple opposition. He doesn’t advocate returning to innocence—that’s impossible. Instead, he posits experience as innocence corrupted by church, state, and rationalist philosophy, yet necessary for achieving higher consciousness. Through understanding contraries—innocence and experience, creation and destruction, lamb and tyger—we can transcend both states.

The progression moves through three stages:

- Thesis: Innocence—untainted, naive, vulnerable to corruption

- Antithesis: Experience—corrupted, knowing, bitter with understanding

- Synthesis: A higher state that reclaims innocence’s vision while retaining experience’s knowledge

Blake advocates imaginative revolution to achieve this synthesis, reclaiming holistic humanity that recognizes both divine joy and worldly suffering without being destroyed by either.

The Role of Institutions

Throughout both collections, Blake consistently critiques institutions:

- The Church: Uses piety to justify exploitation (“Chimney Sweeper”), restricts natural joy (“Garden of Love”), offers false consolation instead of reform (“Holy Thursday”)

- The State: Sends soldiers to die (“London“), allows child labor to flourish, creates legal structures (“chartered” streets) that commodify even freedom

- Economic Systems: Reduce children to commodities, create prostitution and poverty amid plenty, forge mental chains through ideology

These institutions work together to corrupt innocence, creating the fallen world of experience. Yet Blake’s critique isn’t nihilistic—it’s prophetic, calling for radical change.

The Power of Imagination

For Blake, imagination serves as the bridge between innocence and experience, the tool for achieving synthesis. The piper in “Introduction” (Innocence) creates through spontaneous inspiration. The Bard in “Introduction” (Experience) calls forth through prophetic vision. Both use imagination, but the Bard’s vision is tempered by experience’s knowledge of corruption.

Blake himself, through his illuminated manuscripts, demonstrates this synthesis. He combines visual art with poetry, creating multi-layered meaning that engages both intuitive and analytical faculties. The words convey experience’s critique while the images often retain innocence’s beauty, forcing readers to hold both states simultaneously in consciousness.

The Universal and the Particular

Blake moves masterfully between universal archetypes (Lamb, Tyger, Child, Nurse) and particular historical details (chimney sweepers, actual charity children, London’s streets). This allows his work to critique specific 18th-century English conditions while speaking to timeless human struggles. The paired poems show how universal human states—childhood joy, adult responsibility, divine creation—manifest differently in corrupt versus ideal societies.

The Question of Audience

Who are these songs for? Blake suggests “every child”—but he means this symbolically as well as literally. Every person retains an inner child, the capacity for innocent vision. Yet adults, bearing experience’s burdens, need the Bard’s prophetic call to awaken. Blake writes simultaneously for actual children (using simple language and rhyme) and for adults who can perceive the deeper critiques. This dual audience reflects his dual vision.

The Enduring Relevance

Blake died in poverty, largely unknown. Yet his vision has proven remarkably enduring and relevant. His critique of institutional religion, exploitative economic systems, child labor, and ideological control speaks to modern readers confronting similar issues in different forms. His insistence on imagination’s primacy challenges materialist philosophies and scientistic worldviews. His dialectical thinking anticipates later philosophical developments.

Most importantly, Blake refuses to accept corruption as inevitable. The Songs of Experience are not counsels of despair but calls to action. By exposing how innocence becomes corrupted, Blake implicitly argues we can prevent or reverse this corruption. By showing that poverty amid plenty is unnatural (“Holy Thursday”), he insists we can change it. By revealing “mind-forged manacles,” he suggests we can break them through consciousness.

Conclusion: The Marriage of Contraries

Blake’s later work, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, explicitly articulates what the Songs demonstrate: “Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence.”

The Songs of Innocence and Experience are not meant to be read separately but together, each illuminating the other. Innocence without experience is naive, vulnerable, incomplete. Experience without innocence is bitter, cynical, deadening. Together, they create a complete vision of human existence that acknowledges both divine potential and worldly corruption, both childlike wonder and adult knowledge.

Blake calls us to carry innocence’s vision through experience’s trials, to maintain the capacity for joy while fighting against oppression, to see both the Lamb and the Tyger as products of the same creative force, to recognize that the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom, and that everything that lives is holy.

In this synthesis lies Blake’s enduring gift: a path through despair that doesn’t deny suffering’s reality but refuses to let suffering have the final word. The child’s laughter still echoes on the green, even as we hear the chimney sweeper’s cry. The Lamb still grazes peacefully, even as the Tyger burns bright. And somewhere between innocence and experience, if we maintain imaginative vision, we may find our own humanity restored and transcendent.