Introduction

History shows that leading currencies rarely dominate the world stage for long. Reserve currencies typically follow a life cycle: rising with economic strength, and over time, coming under pressure from debt, conflict, and competition.

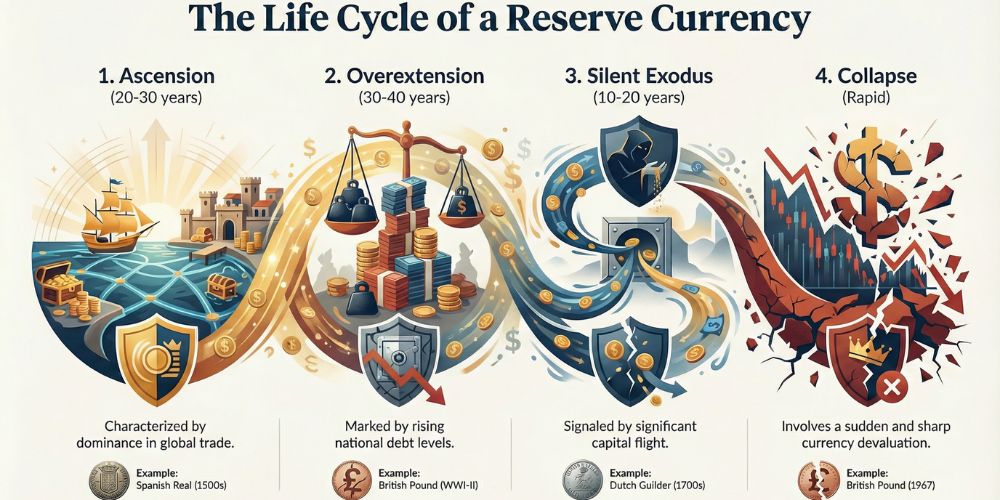

This article uses a four-stage framework, based on Ray Dalio’s Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order, to examine where the U.S. dollar may sit in this cycle today, highlighting that history offers patterns, not guarantees.

Note: Historical patterns can inform, but no cycle repeats in exact form or timing.

The Four Stages of a Reserve Currency

To better understand this dynamic, consider the recurring sequence of stages that leading reserve currencies go through. Historical data show these currencies often enjoy decades of dominance before facing stress and adjustment. While timing varies, many observers identify four broad stages that repeat over long cycles.

Stage 1: Ascension Phase

In the ascension phase, a country becomes a major trading and financial center.

- Strong institutions, innovation, and expanding trade networks drive rapid economic growth during this phase.

- In this period, the country’s currency gains widespread use for international transactions and earns a reputation as a reliable store of value.

- Foreign governments, firms, and investors actively hold that currency and its government bonds as safe, liquid assets.

Historically, Spain in the 1500s, the Dutch Republic in the 1600s, and Britain in the 1800s all experienced versions of this ascension stage as their currencies spread globally.

Stage 2: Overextension Phase

Success often brings new pressures.

- The leading power increases spending on war, welfare, or large domestic programs, which drives public debt to outpace economic growth.

- The government borrows cheaply because trust in its currency allows it to delay difficult fiscal decisions.

- Over time, higher debt levels often prompt more aggressive use of monetary policy, including low interest rates and, in some cases, large-scale money creation.

This phase can last for decades, as the country continues to enjoy prestige, a deep financial system, and strong institutions.

Stage 3: Silent Exodus Phase

If debt and policy imbalances build up, people may gradually change their behavior beneath the surface.

- Large institutions and “smart money” investors begin to diversify into other currencies and into hard assets such as commodities, infrastructure, and real estate.

- Official reserve managers slowly reduce the dominant currency’s share of global holdings, even as it remains the largest single reserve asset.

- This shift typically happens quietly, without immediate crisis headlines, and observers often frame it as prudent diversification rather than open rejection.

For example, the share of the U.S. dollar in disclosed global official foreign‑exchange reserves has remained dominant but has drifted modestly lower over time as some central banks add more euros, yen, or renminbi.

Stage 4: Decline Phase

The final stage does not always mean sudden collapse, but it can involve faster adjustment.

- If confidence erodes sharply, foreign holders may sell the currency or demand higher interest rates, thereby raising the government’s borrowing costs.

- If policymakers rely too heavily on money creation to manage debts and deficits, inflation may rise, reducing the purchasing power of domestic savers.

- In more extreme historical cases, the currency loses its reserve status and is gradually replaced in trade, finance, and official reserves by a competitor.

The pace and severity of this stage vary widely across history, and some countries manage slow, managed adjustment rather than a dramatic crisis.

A Brief Historical Timeline

With this framework in mind, the timeline below illustrates how the four-stage pattern has unfolded in past reserve-currency systems.

| Ascension | 20–30 years | Trade and financial rise | Spanishreal(1500s) |

| Overextension | 30–40 years | Rising debt and conflict | British pound (WWI–WWII) |

| Silent Exodus | 10–20 years | Gradual capital shift | Dutchguilder(1700s) |

| Decline Phase | Often rapid | Devaluation/restructuring | Pound devaluation in 1967 |

Spain’s global role in the 1500s rested heavily on inflows of American silver and gold, but repeated wars and high debts undermined its financial position. The Dutch Republic later lost ground to Britain as capital markets and trade routes shifted to London. In the 20th century, British financial dominance faded under the strain of two World Wars and higher debt, paving the way for the U.S. dollar to become the principal reserve currency under the Bretton Woods system.

Where Does the U.S. Dollar Stand Today?

This framework helps clarify the article’s central argument: while the dollar continues to be the world’s leading reserve currency and is supported by strong institutions, patterns observed in global financial history suggest that even dominant currencies may face turning points as conditions change. Several current trends indicate that the U.S. dollar exhibits features similar to those seen in the later stages of previous currency cycles.

Enduring Strengths of the Dollar

- The dollar accounted for about 58 percent of disclosed global official foreign‑exchange reserves in 2024, far ahead of the euro, yen, pound, and renminbi.

- U.S. Treasury securities remain highly sought after by both official and private investors, with foreign holders owning around one-third of marketable Treasuries in early 2025.

- Deep, liquid capital markets and strong institutions continue to support the dollar’s role as a safe-haven asset.

These factors mean that, despite challenges, people across the world continue to trust the dollar as a store of value and medium of exchange.

Emerging Late‑Stage Features

- U.S. public debt has risen to historically high levels, and net interest costs on the debt have approached or exceeded $ 1 trillion per year, making them one of the fastest‑growing budget items.

- Large asset‑management firms such as BlackRock, J.P. Morgan, and Goldman Sachs have emphasized hard assets and alternative investments in recent outlooks, partly as hedges against inflation and interest‑rate volatility.

- Groups of countries, including the BRICS members, have expanded local‑currency trade arrangements and explored alternatives to dollar-centric payment systems, although these remain small compared with the dollar-based system.

These developments already display some aspects of the “Silent Exodus” and “Overextension” stages, but the scale and speed of any future shift remain uncertain.

Disclaimer: Historical parallels help frame discussion, but they do not guarantee that the U.S. dollar will follow the same path or timing as past reserve currencies.

How Individuals Can Prepare Prudently

For individuals, the goal is not to predict exact dates or dramatic collapse, but to manage risk thoughtfully in a changing environment.

Diversify Beyond a Single Currency

- Consider holding a mix of assets, including foreign‑currency exposure, where regulations and personal circumstances allow.

- Hard assets such as gold, certain commodities, and quality real estate have historically helped preserve purchasing power during periods of high inflation or currency weakness.

Geographic and Asset‑Class Diversification

- Spreading investments across different regions and asset classes can reduce reliance on any single economy or policy regime.

- Long-term investors often combine equities, bonds, cash, and alternatives to balance growth potential with resilience.

Invest in Human Capital

- Skills, education, and adaptability empower people to adjust to new economic conditions, making them among the most resilient forms of wealth.

- In periods of change, people with strong problem-solving and digital capabilities often discover more opportunities, regardless of currency cycles.

Mathematics, Narratives, and Your Next Step

Ultimately, the central argument is that while many public narratives focus on national exceptionalism or the idea that ‘this time is different,’ historical research and long-term patterns point to structural forces—such as debt levels, productivity, demographics, and global competition—as the factors that really drive the direction and eventual turning points of reserve currencies. Short-term emotions matter less than these enduring trends.

An effective way to visualise reserve‑currency status is to imagine a large dam supplying power to a valley. For many years, the structure appears solid and provides huge benefits, but small cracks can develop as pressure grows. Regular inspection, maintenance, and cautious behavior by those living downstream make far more difference than sudden panic.

Ultimately, readers should not only consider whether the global currency cycle will eventually turn, but also how prepared they are if it does. Review your savings, investments, and skills with this long‑term perspective in mind, and seek qualified financial advice where appropriate to build resilience.