Introduction

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d by Walt Whitman is one of the most effective elegies that America has ever produced, written in reaction to the assassination of presidential figure Abraham Lincoln in April 1865. Written during the last months of the Civil War, when the whole country is in a state of deep mourning, the poem transcends the theme of personal sorrow to confirm a countrywide trauma and its resistance to meaning in the loss of their leader. Originally published in the fall of 1865 as part of Sequel to Drum Taps, it combines a sequence of symbols of nature, including lilacs in a dooryard, a fallen western star, and a solitary hermit thrush, into a common ceremony of loss and recuperation. Rather than contemplating the brutality of Lincoln’s death, Whitman transforms the president into an unknown beloved to make the elegy address universal losses and gradual recovery. The free verse that Whitman employs in his work defies the traditions of the elegiac and the established rhyme and meter in favor of a democratic, inclusive voice that lists American landscapes, memories, and visions. This elastic shape allows him to embrace both extremes of sorrow that are intimate with the cyclic energy of life, which describes death not as a sudden conclusion but as a natural transition, a cool embrace of enfoldment that connects the living world. The emotional richness, the richness of symbols, and the constant rhythmic flow of the poem continue to address readers today, contributing to Whitman‘s status as one of the key poets of American democracy.

The Poet Behind the Poem

Walt Whitman was born on May 31, 1819, in West Hills, Long Island, and he grew up in Brooklyn, which was in financial crisis. His formal education ended at the early age of eleven, and his boyhood was spent in training as an apprentice printer, an elementary school teacher, a newspaper reporter, and an editor. It is these occupations of ordinary Americans that would give him a democratic perspective and an unusually intimate view of the country’s social diversity. Some of the earliest essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson, such as “The Poet” (1844), which advocated a uniquely American poetry, emboldened Whitman to begin the work that would make his life. He self-published Leaves of Grass, a thin but revolutionary book of a dozen untitled poems that exalted democracy, nature, sensuality, and the body in brash and experimental free verse, in July 1855. No name of the author appeared on the title page of the book, but a portrait of Whitman in workingman clothes was engraved.

Emerson declared the book the most remarkable work of wit and wisdom and wrote to Whitman, “I welcome you to a great career.” Its openness toward the body and sexuality offended the sensibilities of many other critics, and others denounced it as obscene. Whitman never gave up, continuing to revise and expand Leaves of Grass through nine editions, eventually transforming the originally small book into a megalithic publication of close to 400 poems when he died. Whitman also worked in military hospitals in Washington, D.C., during the Civil War, where he volunteered to look after wounded men. These were the years that left a deep imprint on his writing, making it poignant, realistic, and conscious of suffering and death. In 1873, he died on March 26, 1892, in Camden, New Jersey, after a stroke had partially paralyzed him. His contributions to American poetry have been enduring, with continued appeal to modernist authors like Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg and have given him a reputation that has been repeatedly repeated, making him widely known as the father of free verse.

Understanding the Title

The title “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomd” clearly establishes the poem’s setting and atmosphere right from the beginning. Lilacs were blooming in the northeastern United States when Lincoln was killed on April 14, 1865. Whitman recalled, “I remember where I was stopping at the time, the season being advanced; there were many lilacs in full bloom… I find myself always reminded of the great tragedy of that day by the sight and odor of these blossoms. It never fails.”

The mere ending of the term last in the title simultaneously represents multiple meanings. It refers to the lilacs of that spring, the last ones Lincoln will see. It also alludes to repetition, because, in all subsequent springs, the flowers return, bringing the renewed desire to weep. Such a seasonal pattern of grieving shows how loss weaves into the fabric of life and returns every spring, as the lilacs do. The poem grounds itself in everyday American life rather than the pomp of the political situation, using the small domestic place of the dooryard. In his setting, Whitman selects a plain farmhouse dooryard to democratize grief, implying that ordinary people everywhere, not officials and the elite, grieved Lincoln. The title silently enters the rite of remembrance in Whitman, heralding a poem in which loss constantly intertwines with the tenacious existence of life.

Historical Background: A Nation in Mourning

To appreciate this elegy, it helps to realize the time during which it emerged. On the night of April 14, 1865, just five days after Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House, President Lincoln attended a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. There, the actor John Wilkes Booth shot him in the head; Lincoln died the following morning, becoming the first assassinated American president. The news devastated the country. Later, during Specimen Days, Whitman recalled that the news of the murder arrived very early in the morning while he was visiting his mother in Brooklyn. Mother served breakfast, lunch, and supper as usual, but neither of us ate even a mouthful of food all day. We both drank half a cup of coffee; that was it. We spoke little.

Lincoln commenced his 1,700-mile funeral procession by rail between Washington and Springfield, Illinois, on April 21. The train crossed great cities, and millions mourned along its path. This cortege, with its draped coffin slowly pacing the streets amid silent crowds, directly influenced the imagery of Whitman’s poem. The funeral casket, riding through the spring scenery, becomes a major theme, set against the fields of flowers to contrast the countryside with the ugly reality of death. Whitman had long admired Lincoln. Just a couple of weeks earlier, he observed the president’s second inauguration. During Specimen Days, he wrote that Lincoln looked so worn and exhausted, with lines of great responsibilities cut deep upon his face, yet he still carried all the old goodness, tenderness, sadness, and cunning shrewdness. In an 1863 letter, Whitman said, I believe in Lincoln to the end; not many know what rocks and quicksand he has to navigate.

At the time Lincoln was murdered, Whitman was already planning to publish Drum-Taps, his collection of Civil War poems. Upon hearing of the assassination, he put the publication on hold and hastened to compose “Hush’d Be the Camps To Day” on April 19. This was, however, a short monument, and it was not content with this meager praise. This would lead to When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomd later that year in the collection titled ” Sequel to Drum-Taps with another Lincoln poem of his, “O Captain! My Captain!”

The Individual to Universal View of the Speaker

A first-person speaker narrates the poem- ‘I’– that is apparently Whitman but extends to the group. Such a close perspective plunges the readers into the emotional path of the speaker: “I mourn’d, and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring.” There is a confessional tone that calls for empathy. It sets up the poem’s main conflict between personal and national sorrow.

The ‘I’ in the poem develops and grows as it progresses, becoming a sort of visionary prophet. In the initial passages, the speaker is in the clutches of sorrow, is helpless in the hands of a sadist, but the view gradually expands. He sets out to list American landscapes, spires of Manhattan, rivers of Ohio, prairies of Missouri, in panoramic views reminiscent of his Leaves of Grass style: And I saw askant the armies. The change is indicative of Whitman’s democratic spirit: the individual ‘I’ holds multitude, and the demise of one man is consistent with a broader human and national condition.

More importantly, Lincoln is not mentioned in the poem. Whitman simply calls it “I love and the dead one there,” which makes his subject universal. The unknown lover might be any individual lamented by any grieving lover. This makes the poem accessible to anyone who has experienced loss. The point of view has two purposes. It maintains the personal grief and extends to include communal trauma. This makes one elegy a communal healing ritual.

Mood and Tone: Melancholy to Acceptance

The atmosphere of the poem is extremely melancholic. It maintains the privacy of personal grief but extends to the nationwide trauma by the speaker’s tears at night, and the bleeding throat of the thrush expresses the powerlessness of the speaker. Visions and darkness recur: the star subsides into a black murk. Visions and darkness recur: the star subsides into a black murk, death is a dark mother, and thoughts that entrap the speaker in their grip plague him or her, keeping him or her powerless. In this darkness, Whitman gradually develops redemptive peace. The poem of love transforms the fear of death into a lovely, soothing death as it flows through. It comes with serene footness, with certain-winning arms. The thrush’s song, supposedly attributed to a bleeding throat, is transformed into a song of death, with its streams of the yellow gold of the beautiful, lazy, sinking sun. This slow transition from suffering to acceptance makes the mood sound both muted and ecstatic.

The tone is elegiac, though also quite celebratory, lamenting but also asserting life. The diction Whitman employs in his poem, in which he speaks to the death and the dead, “you,” generates the feeling of compassionate universality. He does not just give flowers to the coffin of Lincoln but to the coffins of you all, O death, and brings honor to the untold dead, and democratizes grieving. This triadic melancholy and eventually optimistic tone embodies the main idea of the poem: the spring This triadic melancholy and, eventually, optimistic tone embody the poem’s main idea: the spring will come no matter how long the winter lasts, and life will be in its cycles of death and rebirth, bringing not only hopelessness but also a difficult yet gained strength.

Exploring the Poem’s Central Themes

Death as Both Destroyer and Liberator

At its core, the poem wrestles with death’s double nature. Lincoln’s assassination marks a national rupture—the violent loss of a beloved leader at a moment of fragile peace. Yet Whitman refuses to present death as only destructive. He frames it within nature’s recurring cycles, where spring’s lilacs announce both grief and renewal. Death becomes part of life’s continuum rather than its simple opposite.

In Section 14’s climactic “carol of death,” the speaker addresses death directly:

“Come lovely and soothing death,

Undulate round the world, serenely arriving.”

Here death is personified as a gentle deliverer, offering “bliss” and “cool‑enfolding arms.” This largely Transcendentalist acceptance challenges Victorian fear of mortality, suggesting that death is a passage rather than a final stop—a release of the soul into the “fathomless universe.”

Collective Mourning and Democratic Inclusivity

Though prompted by Lincoln’s death, the poem steadily broadens its sympathy to encompass all who suffer. The speaker moves from mourning one “comrade lustrous” to envisioning Civil War dead—“battle‑corpses” with their “white skeletons of young men”—and finally to recognizing that “the living remain’d and suffer’d.” This widening arc from individual to collective mourning reflects Whitman’s democratic vision: in death, all are equal, and all deserve remembrance.

The poem’s long catalogs of American landscapes—from Manhattan to the prairies, from ocean winds to farmlands—help reunite a fractured nation through shared geography and shared grief. By omitting Lincoln’s name and the specific details of the assassination, Whitman ensures that the poem speaks beyond a single historical moment. This deliberate generality makes the elegy resonate as a meditation on loss itself, accessible across times, places, and circumstances.

Healing Through Art and Memory

Central to the poem is the idea that art—especially song—offers a path through grief. The hermit thrush’s “death’s outlet song of life” becomes a model for the poet’s own work. Just as the bird sings alone from the swamp, the poet raises his own “tallying song,” turning raw emotion into shaped verse that can be shared and understood.

Memory also plays a crucial role. In the final section, the speaker admits that the poem’s symbols will remain with him always: “Lilac and star and bird twined with the chant of my soul.” Instead of trying to forget or outgrow grief, he weaves it into his identity. Each spring the lilac returns, stirring memory again, yet this repetition becomes less a burden than a kind of ritual—a way of keeping the beloved present through ongoing cycles of remembrance.

The Poem’s Structure and Development

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d consists of sixteen numbered sections and 206 lines. Written in free verse, it abandons regular stanzas for fluid, prose‑like units that follow the organic movement of feeling and thought. This structure itself suggests a democratic gesture, trading the tight constraints of meter and rhyme for a more inclusive, breath‑based rhythm.

The poem unfolds as a ritual journey from isolation to communion, from despair toward a kind of ecstasy. Early sections introduce the three central symbols: the lilac in the dooryard, the fallen western star (Venus), and the hermit thrush singing from the swamp. These figures recur and intertwine throughout, each taking on new shades of meaning as the poem moves forward.

The middle sections trace the funeral procession through spring landscapes, setting death’s passage against unfolding seasonal abundance. Whitman catalogs violets, wheat fields, apple blossoms, and other signs of American plenty, building a counterpoint between life’s fullness and mortality’s finality. This juxtaposition heightens the emotion: the world keeps blooming, seemingly indifferent but also strangely consoling in its persistence.

Section 14 provides the emotional climax with its extended “carol of death,” where the speaker finally stops resisting and accepts mortality as natural and even beautiful. The language there turns almost ecstatic, at times nearly erotic:

“Lost in the loving floating ocean of thee,

Laved in the flood of thy bliss O death.”

This moment marks a psychological shift from fighting grief to consenting to it.

The final section returns to the dooryard, offering cyclical closure rather than a neat, linear ending. The speaker releases the symbols yet admits they will remain with him:

“I leave thee lilac with heart‑shaped leaves,

I leave thee there in the door‑yard, blooming, returning with spring.”

The poem ends by affirming that mourning is not something to finish and leave behind, but something to carry forward within ongoing life—a kind of wisdom that continues to resonate across cultures and eras.

Whitman’s Literary Techniques and Symbolism

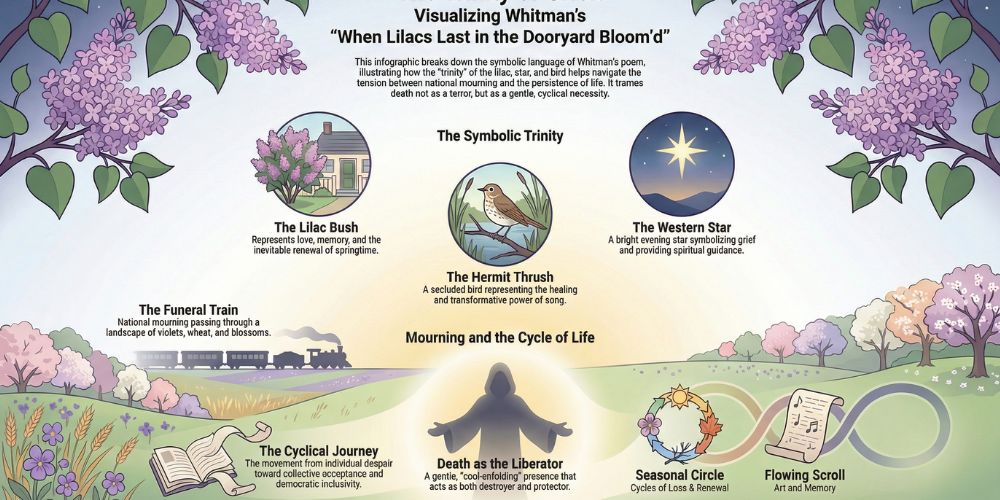

Symbolism: The Trinity of Lilac, Star, and Bird

The poem’s three central symbols operate on multiple levels simultaneously:

The Lilac represents enduring love and memory, with its “heart-shaped leaves” suggesting affection that persists through seasons. Its purple color evokes both passion and mourning. As a perennial plant blooming each spring, it symbolizes resurrection and renewal. The speaker offers a lilac sprig to the coffin as tribute—a gesture both intimate and democratic, as he extends the offering to “coffins all.”

The Western Star (Venus) represents the fallen president—“O powerful western fallen star!”—but also idealized leadership, hope, and guidance now lost. Whitman noted that Venus was indeed prominent in the western sky during Lincoln’s final months, seeming to carry portent. Its disappearance into “the netherward black of the night” mirrors Lincoln’s death and the nation’s plunge into uncertainty.

The Hermit Thrush represents the artist’s solitary voice and the song of reconciliation with death. Its “bleeding throat” suggests the pain of artistic creation, while its carol from the swamp’s seclusion mirrors the poet’s isolated labor to transform grief into art. The thrush sings “death’s outlet song of life,” suggesting that from death comes renewed understanding and creative expression.

Imagery and Figurative Language

Whitman employs rich sensory imagery throughout. Visual images abound: “floods of the yellow gold of the gorgeous, indolent, sinking sun,” “violet and purple morning,” “apple-tree blows of white and pink.” These vivid pictures ground abstract grief in concrete, observable beauty.

Olfactory imagery is equally important. The “perfume strong I love” of the lilacs recurs as a triggering scent, while the speaker promises to “perfume the grave of him I love” with sea-winds. Scent, more than any other sense, links directly to memory and emotion, making it particularly suited to elegy.

Personification transforms abstract death into “dark mother always gliding near with soft feet” and “strong deliveress,” endowing it with agency and even nurturing qualities. This technique makes death less terrifying, more comprehensible as part of nature’s cycle.

Biblical allusions suffuse the text, particularly in the phrase “Prais’d be the fathomless universe,” which echoes Psalms’ cosmic hymns. These references connect Whitman’s elegy to centuries of sacred poetry while secularizing traditional religious consolation into a more pantheistic, nature-based spirituality.

Free Verse and Rhythm

The poem’s free verse—unrhymed lines of varying lengths—was revolutionary for its time. Whitman creates rhythm through repetition and parallelism rather than traditional meter. Anaphora (repeating opening words) structures many passages:

“O powerful western fallen star!

O shades of night—O moody, tearful night!”

This technique creates incantatory power, evoking both biblical prophecy and operatic aria.

Long catalogs—lists of American places, natural phenomena, human activities—create a sweeping, panoramic effect that mimics the funeral train’s journey and the speaker’s expanding consciousness. These lists also democratize the verse, giving equal weight to “Manhattan’s streets” and “Ohio’s shores,” to “the mother” and “the musing comrade.”

The rhythm varies from short, exclamatory bursts (“O death, I cover you over with roses”) to long, flowing lines that build in waves (“With the show of the States themselves as of men and women changing… / With processions long and winding and the flambeaus of the night”). This variety mirrors the emotional progression from sharp grief to encompassing acceptance.

Essential Lines from the Poem

“Ever-returning spring, trinity sure to me you bring,

Lilac blooming perennial and drooping star in the west,

And thought of him I love.”

This trinity encapsulates the poem’s core symbolism and establishes grief as seasonal and cyclical. Spring returns inevitably, always bringing these three elements together: the blooming lilac, the evening star, and thoughts of the beloved dead. The word “trinity” evokes religious resonance while secularizing it—nature’s cycles replace Christian doctrine as the framework for understanding death and remembrance. This passage frames mourning not as something to overcome but as something that recurs with each spring, woven eternally into the natural world.

“Come lovely and soothing death,

Undulate round the world, serenely arriving, arriving,

In the day, in the night, to all, to each.”

These lines mark the emotional turning point of the poem, where death transforms from terror to embrace. By personifying death as “lovely and soothing,” Whitman inverts conventional fear, presenting it instead as a gentle wave that “undulates” naturally across the world. The repetition of “arriving” creates a sense of inevitability without dread, while “to all, to each” democratizes death—it comes equally to presidents and common people, uniting all humanity. This passage offers cathartic release, shifting from resistance to acceptance and revealing death as part of life’s pattern rather than its opposite.

“The living remain’d and suffer’d, the mother suffer’d,

And the wife and the child and the musing comrade suffer’d,

And the armies that remain’d suffer’d.”

This catalog of survivors highlights a crucial insight: death may bring peace to the deceased, but the living continues to bear grief’s weight. By listing “mother,” “wife,” “child,” and “comrade,” Whitman creates an inclusive portrait of a nation in mourning, acknowledging that loss ripples outward through families and communities. The repetition of “suffer’d” emphasizes ongoing pain, refusing to offer false consolation. Even “the armies that remain’d suffer’d”—those who survived the war carry trauma forward. This passage grounds the poem’s philosophical acceptance of death in honest recognition of grief’s persistence among the living.

Critical Analysis: Innovation and Influence

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d repeats the pastoral elegy, although it appeals to its traditions. Classical elegies–of Lycidas with Milton, of Adonais with Shelley–swing away out of lament, through interrogation, to the reassurance of Christian immortality or poetic immortality. Whitman maintains this emotional trajectory and dramatically changes the materials. He does not offer classical shepherds or a heaven-bound soul, but rather presents American landscapes and a Transcendentalist view of death as a natural passage.

These sixteen parts help the poem follow a sort of spiritual path as the cramped dooryard traces into a wide, cosmic horizon, just as the funeral train takes a long route, and as the inner growth of the speaker unfolds. Grief appears initially paralysing, – “O cruel hands that hold me powerless”—but gradually the thrush’s song opens a path toward release: “Lost in the loving floating ocean of thee.” This transition between immobility and a measured transcendence catharsis without pretending that grief is merely finished.

Whitman’s symbolism is very advanced. The lilac, which has been picked out of the commonplace earth, is a democratic gift of love, not to Lincoln only, but to ‘coffins all’, and he spreads the elegy to the dead of the war, who lie nameless in their graves. The western star (Venus) symbolizes the death of romantic leadership, and the hermit thrush represents the lone artist whose music joins personal suffering and general acclaim. These pictures repeat and overlap, ending in the ‘fragrant pines’ of Section 16, where they come together in a protective bower of memory, suggesting a sense of combination rather than distinction.

Another theme that is challenged by the poem is the death of the Victorians. Where Tennyson’s In Memoriam seeks Christian comfort in union after death, Whitman derives it from immanent transcendence, death as “cool enfolding” happiness in the cycles of nature. Such substitution of supernatural for natural consolation is characteristic of Transcendentalist ideology, specifically Emerson’s concept of death as a reunion with the Over Soul.

The way Whitman treats war is also very important. The images of “battle corpses”, “tattered flags”, and “white skeletons” in section 15 show no glory but silent peaceful rest. The fact that he highlights the pain of those who survived rather than martial heroism makes him doubt the mythology of war and shows respect for soldiers’ sacrifice. This anti-war humanism foreshadows subsequent anti-war poetry, including that of Wilfred Owen and the Vietnam War writers.

The poem’s rhythm is free verse, and this style is stylistically accurate, as the rhythm of grief also rises and falls. Whitman does not rely on rhyme in his poetry but uses breath-based pulse, echoing heartbeats and funeral music, making high art more accessible to ordinary readers. A combination of common words (“dooryard”, “sprig”) and grandiose sentences (“fathomless universe”) creates a clearly American poetic voice.

The power of the poem has a far-reaching impact that extends beyond its time of origin. Its rejection of a clean-cut ending — grief with each spring — anticipates the modern psychology of mourning as a process of continuous integration rather than a neat ending. Its democratic inclusiveness and intimate and expansive “I” assisted in the development of the confessional poets, including Robert Lowell, who have reiterated its ritual of collective memory in the poem “For the Union Dead”. Even more recent laments, such as September 11th poems or the laments of the COVID era, follow the tradition of Whitman, who transforms collective trauma into song, but he does so by using the singular, familiar voice.

Relevance to Modern Poetry and Literary Innovation

In his writing, Whitman changed the trend in American poetry. By abandoning the strict meter and rhyme patterns of most Romantic predecessors, he was leading the way to a form that suited American experience: sprawling, democratic, and inclusive. Where Wordsworth tends to remain in time-honoured stanza structures, and Tennyson in thought tracks out in very stringently echelon lines, Whitman‘s free verses allow thought to move much closer to the direction of the stream of thought itself.

This formal discontinuity leads directly to the experiments of modernism. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land shows clear debts to Whitman in its catalogs and juxtapositions, its blend of high and low diction, and its use of recurring symbols that gather meaning over time. Ezra Pound, though initially skeptical of Whitman, eventually acknowledged his role in freeing poetry from strict European patterns.

The queer-inflected intimacy in the poem, such as the phrases he uses to express his love for him and the moments he speaks of holding hands with comrades, also anticipates subsequent confessional and LGBTQ+ poetry. In the poem Howl, Allen Ginsberg publicly stated that Whitman was a spiritual ancestor, modifying Whitman’s prophetic tone and enumerations of democracy. This tradition continues with contemporary poets addressing issues of racial injustice and the climate crisis with a Whitmanian we.

In the context of trauma poetry, “Lilacs” sets a precedent. It resonates with the recent elegies on gun violence, pandemic loss, and perpetual social injustice by its cyclical nature, which recognizes that grief does not resolve itself in a tidy manner but returns. The communal I that Whitman uses is modified by poets like Yusef Komunyakaa in his poems about Vietnam and Claudia Rankine in her book Citizen to represent and address communities of non-hegemonic people.

Most importantly, Whitman demonstrated that American poetry did not have to emulate European standards but could create its aesthetic out of local resources, simple landscapes, colloquial language, and democratic principles. This claim of cultural autonomy remains in the service of poets with American and contemporary voices of their own. Whitman was very literal, which is why, in our era of social media and digital forms, a mix of accessibility and emotional outspokenness is particularly pertinent to him.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom turns the Civil War trauma into a long-term reflection on grief, memory, and strength. Whitman follows griefs with its journey through powerless tears to some sort of happy submission with the help of three symbols that lilac, star, and thrush as his trinity, implying that mourning can be carried and blended instead of being conquered.

Innovations in the poem, the democratic breath of free verse, the catalogs across the continent, the redefinition of death as terror transformed into a cool enfolding hug, and so forth, served to break the elegy tradition and gave way to the emerging tradition of modern American poetry. But its power is founded in no less emotional candor than in formal daring. Whitman does not want to be comforted so easily; he acknowledges that every new spring will awaken old memories and that people who are alive are still suffering even though the dead are resting.

With the world devoid of unity and full of frequent state defeats, Whitman is very relevant to our time. The fact that death undulates, according to him, to all, to each, is an emphasis on the humanity shared across a political and social boundary. His example demonstrates how poetry might transform individual loss into community ceremony, providing one method of coping with trauma.

The lilac sprig is left, after all–an oval stamp that when we sing of the dead, we are singing of the living. The blossoming of each spring rekindles not only the flowers but the memory, connection and hope. By this, we see that the legacy of Lincoln, and the continuous test-run of American democracy, continues to this day in every recurring dawn, and every dooryard where lilacs have grown.